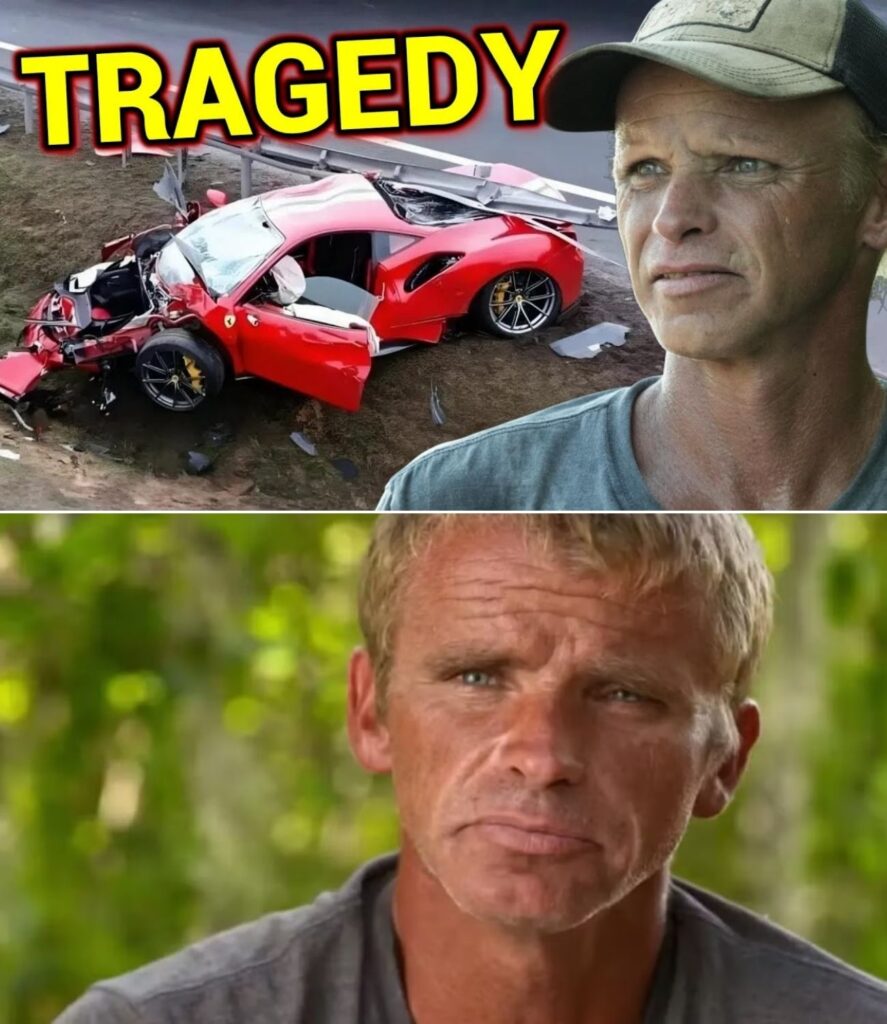

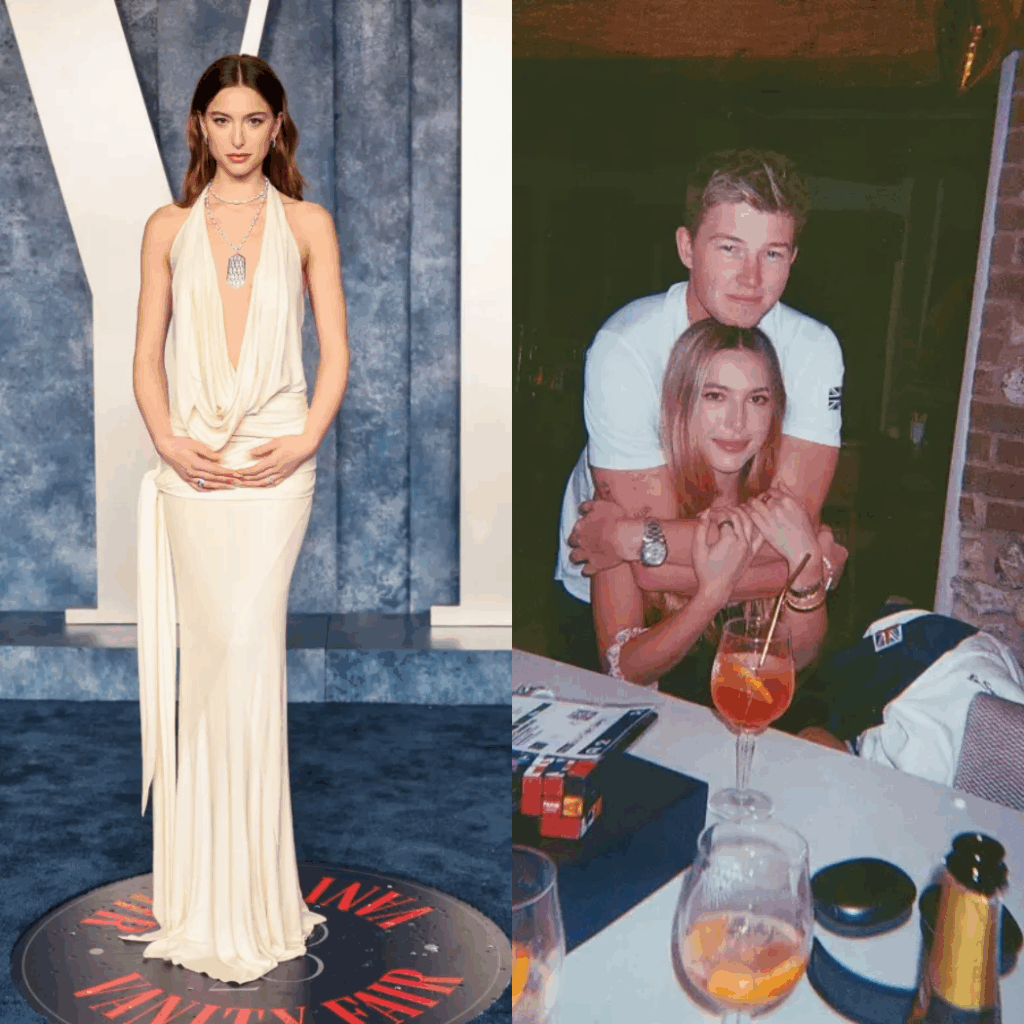

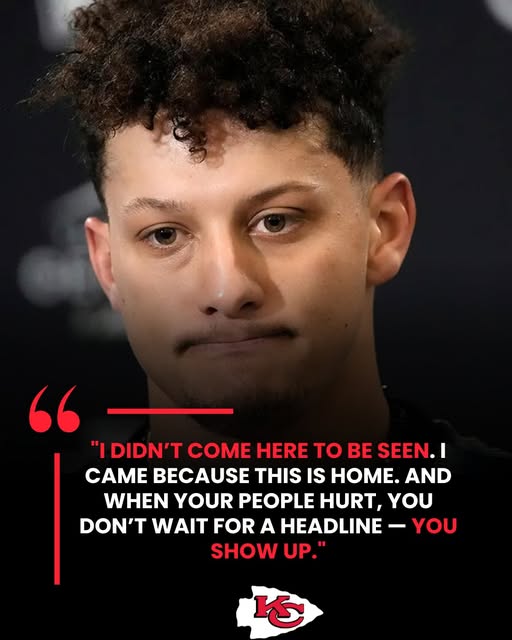

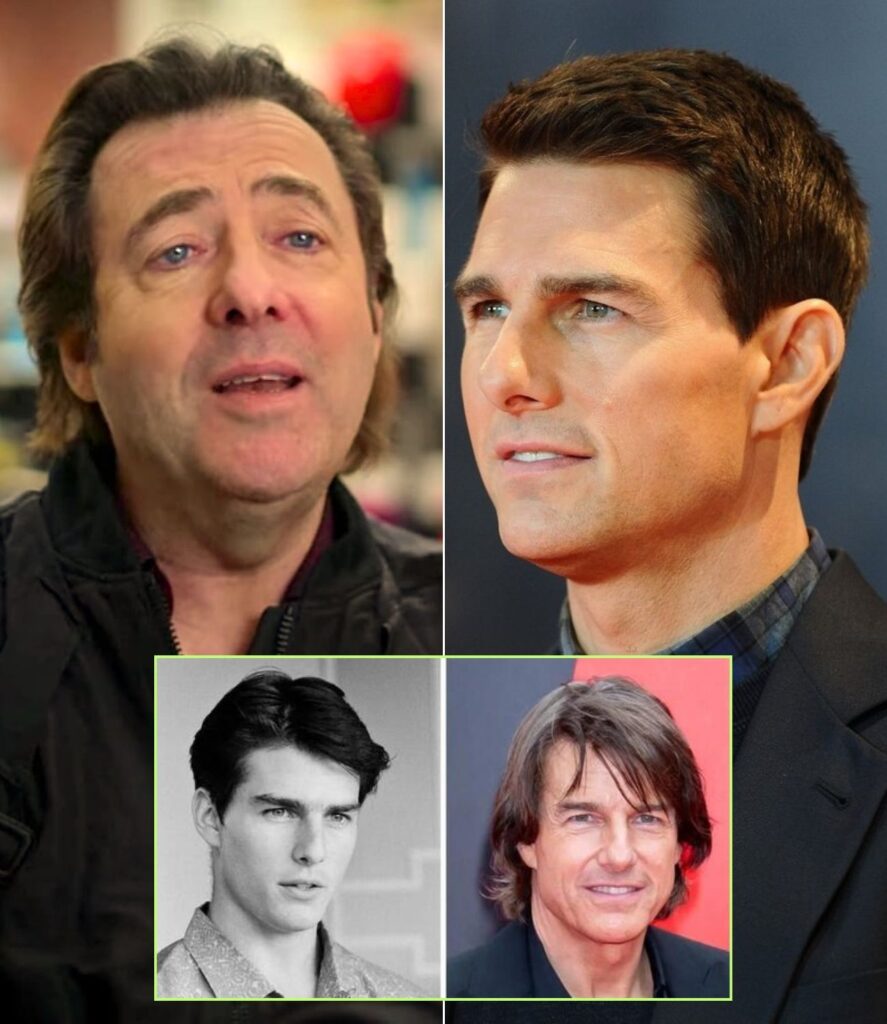

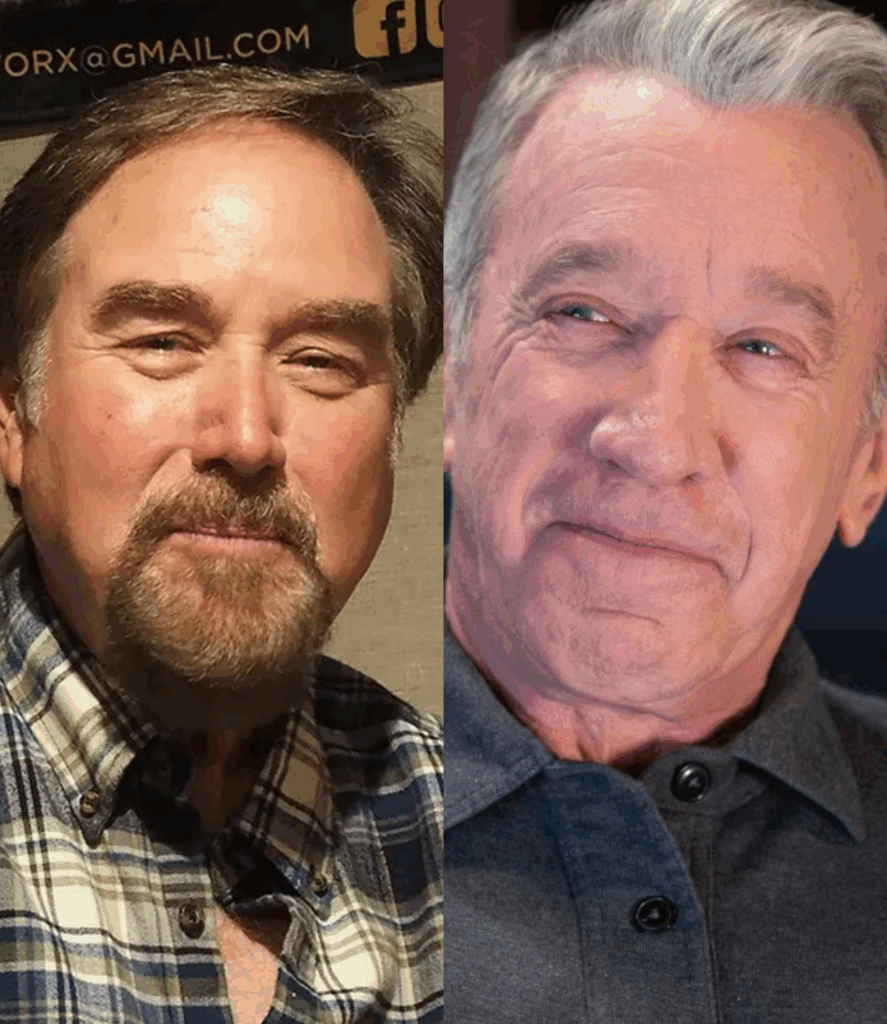

Before Creating Yellowstone, Taylor Sheridan Lived a Life So Shocking and Ruth-less — From Poverty, Dark Secrets, and Unexpected Hustles to Power Moves That Changed Hollywood Forever.

Before Creating Yellowstone, Taylor Sheridan Lived a Life So Shocking and Ruth-less — From Poverty, Dark Secrets, and Unexpected Hustles to Power Moves That Changed Hollywood Forever.

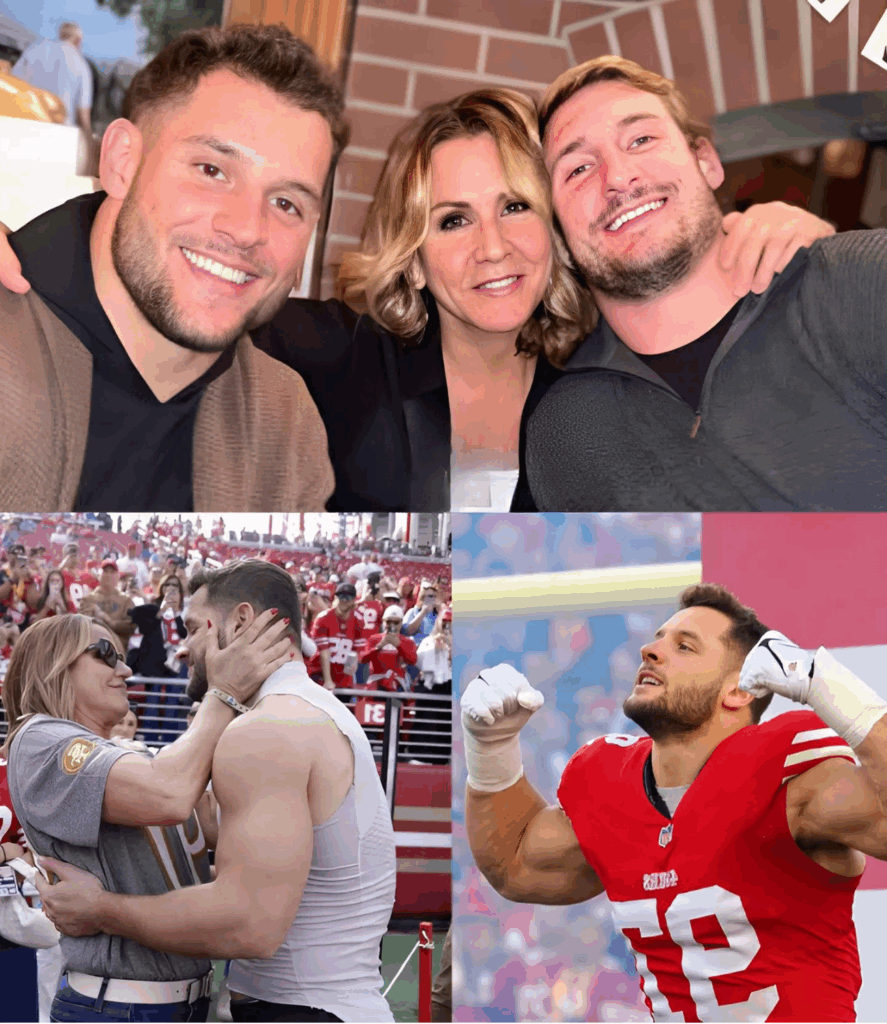

Taylor Sheridan is not your average Hollywood screenwriter. In fact, he’s one of the few who can seamlessly move between riding horses on a remote Texas ranch and commanding the attention of millions through some of the most-watched television dramas in recent history. Known best as the mastermind behind Yellowstone, Sheridan’s real-life story is just as dramatic and compelling as the gritty neo-Westerns he writes.

Let’s dive deep into the wild, rugged, and surprising life of Taylor Sheridan—a former actor, working cowboy, self-taught writer, and the man who redefined modern Westerns.

Humble Beginnings: A Cowboy at Heart

Born in Cranfills Gap, Texas, a tiny town with a population of fewer than 300 people, Taylor Sheridan grew up on the edge of poverty. Raised by a single mother on a ranch, his early years were defined by rural hardship and a deep connection to the land. He didn’t grow up dreaming of red carpets or Oscars; he grew up fixing fences, breaking horses, and helping neighbors.

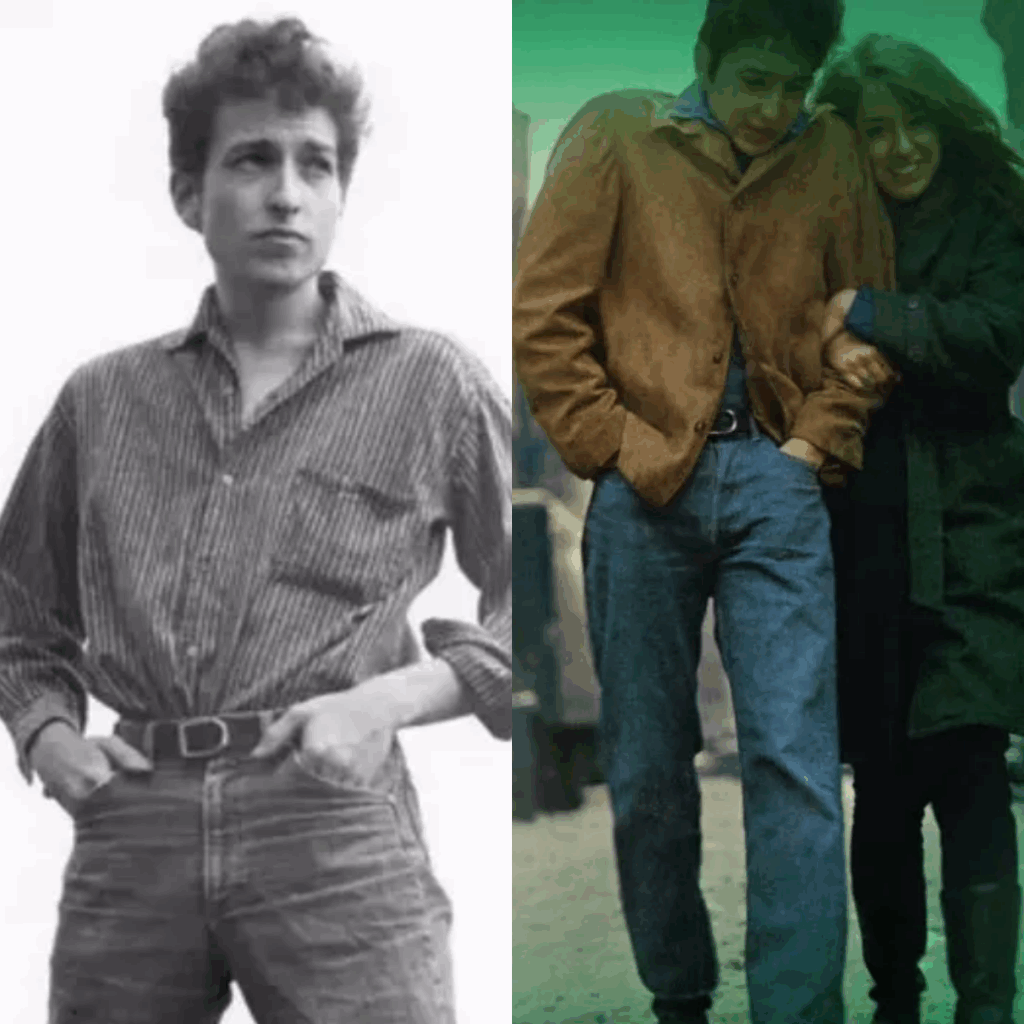

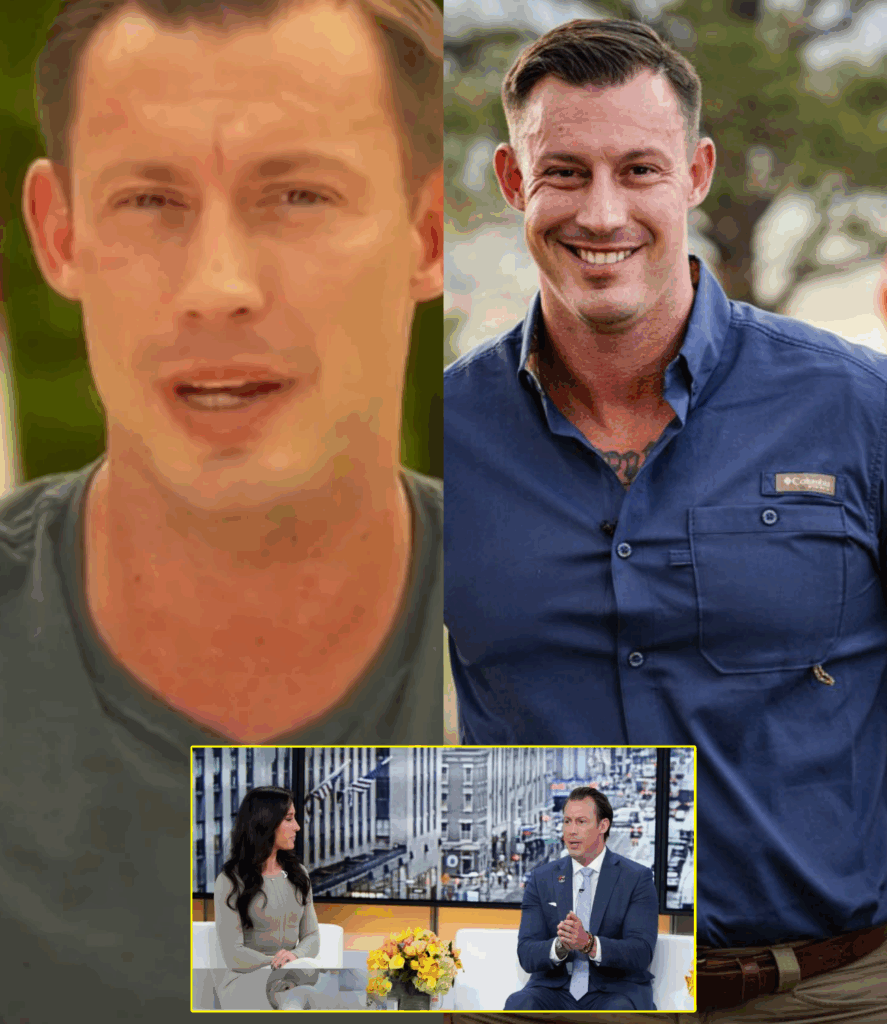

Sheridan often describes himself as a “misfit” during his youth. He briefly attended Texas State University but eventually dropped out and moved to Austin, where he scraped by doing odd jobs—painting houses, laying tile, and working as a cowboy. One day, while searching for work at a shopping mall, he was scouted by a talent agent. That moment would change his life forever.

A Struggling Actor’s Grind

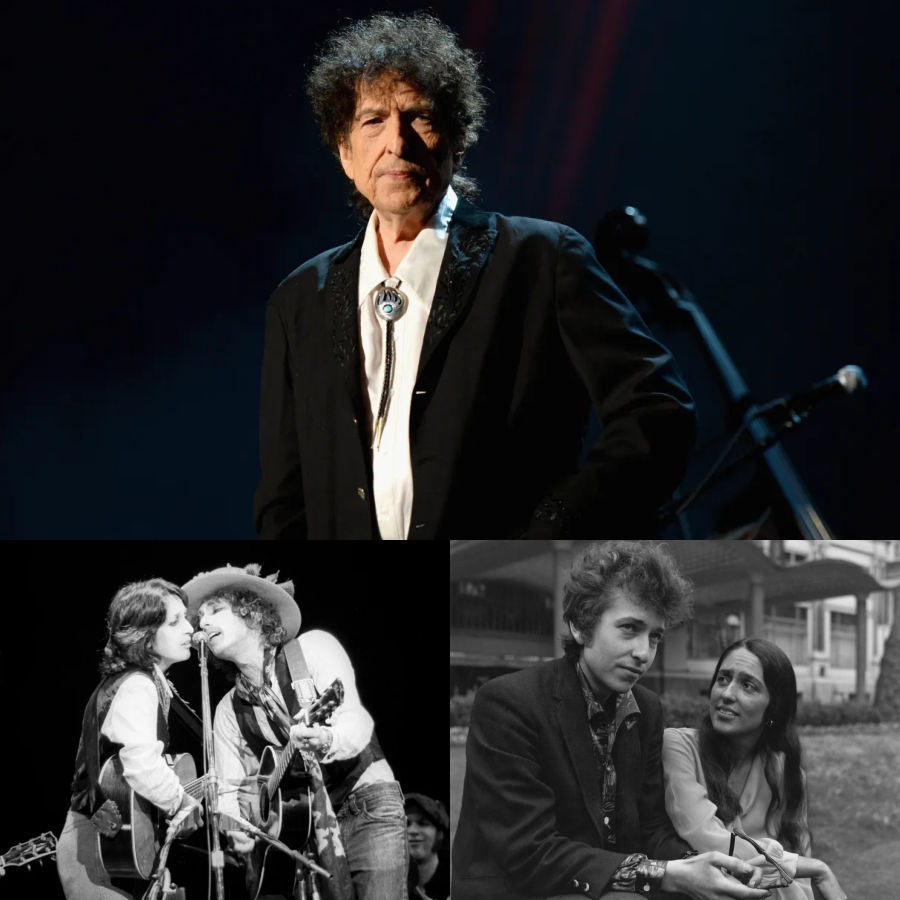

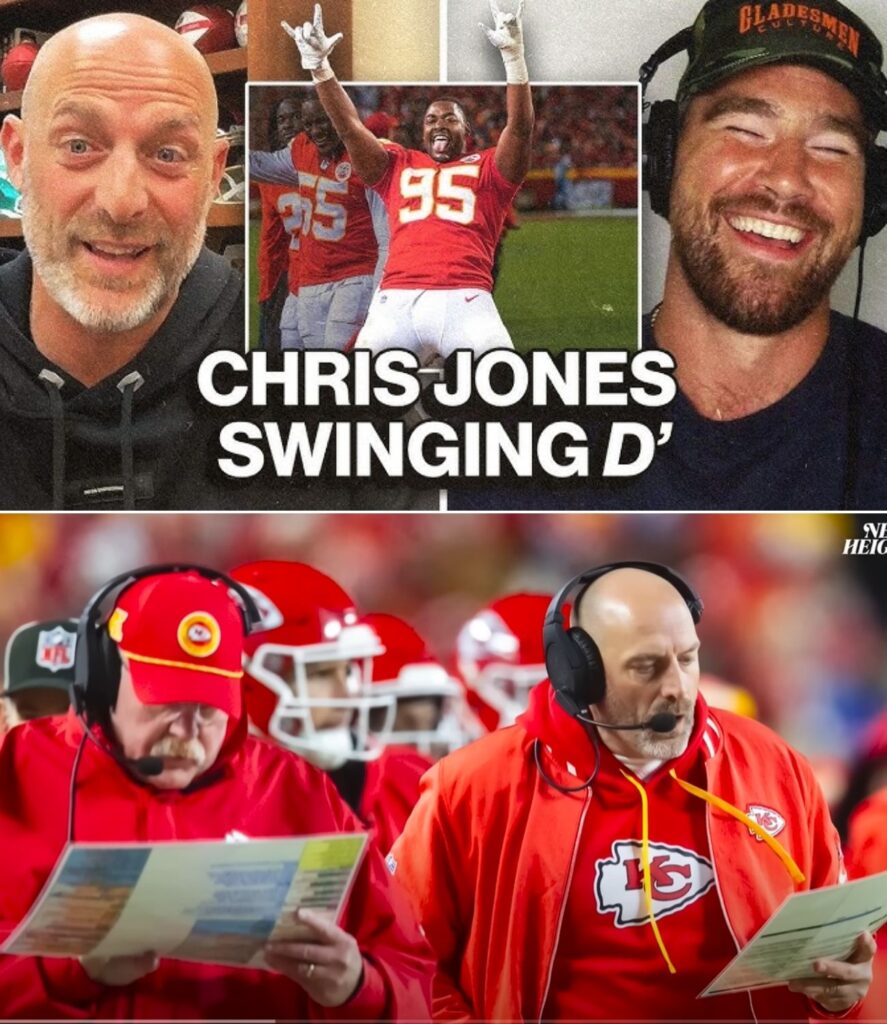

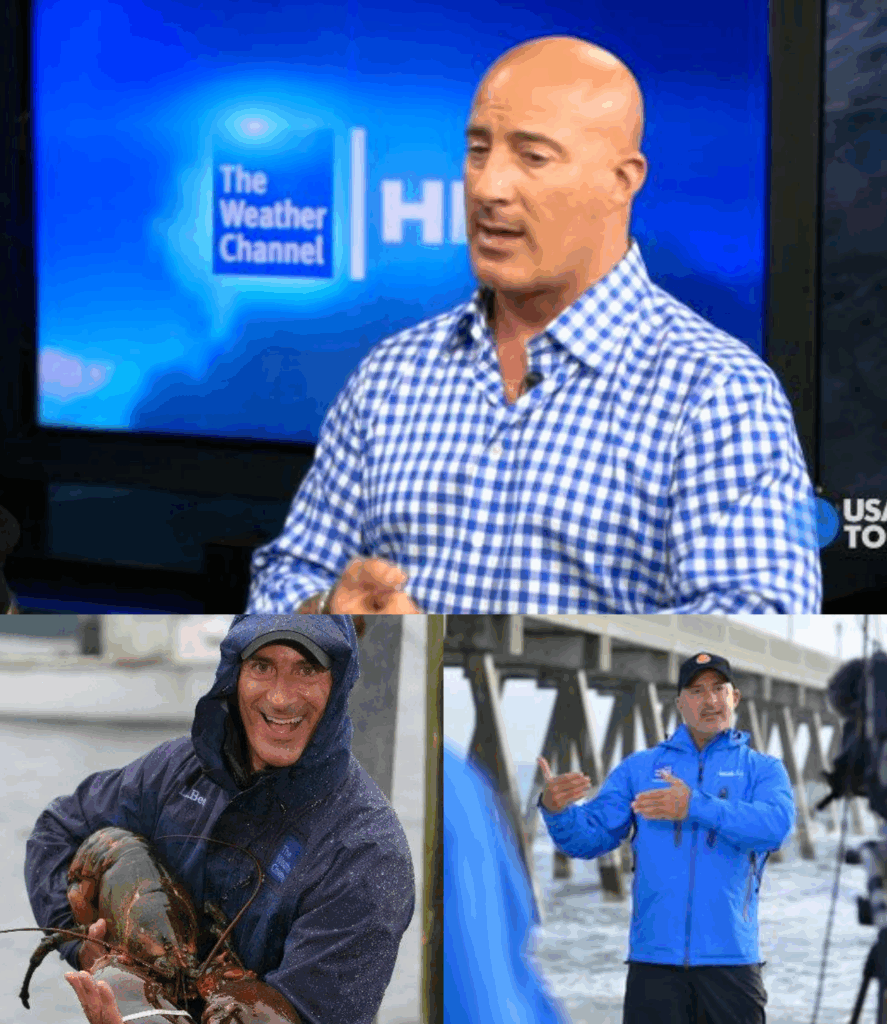

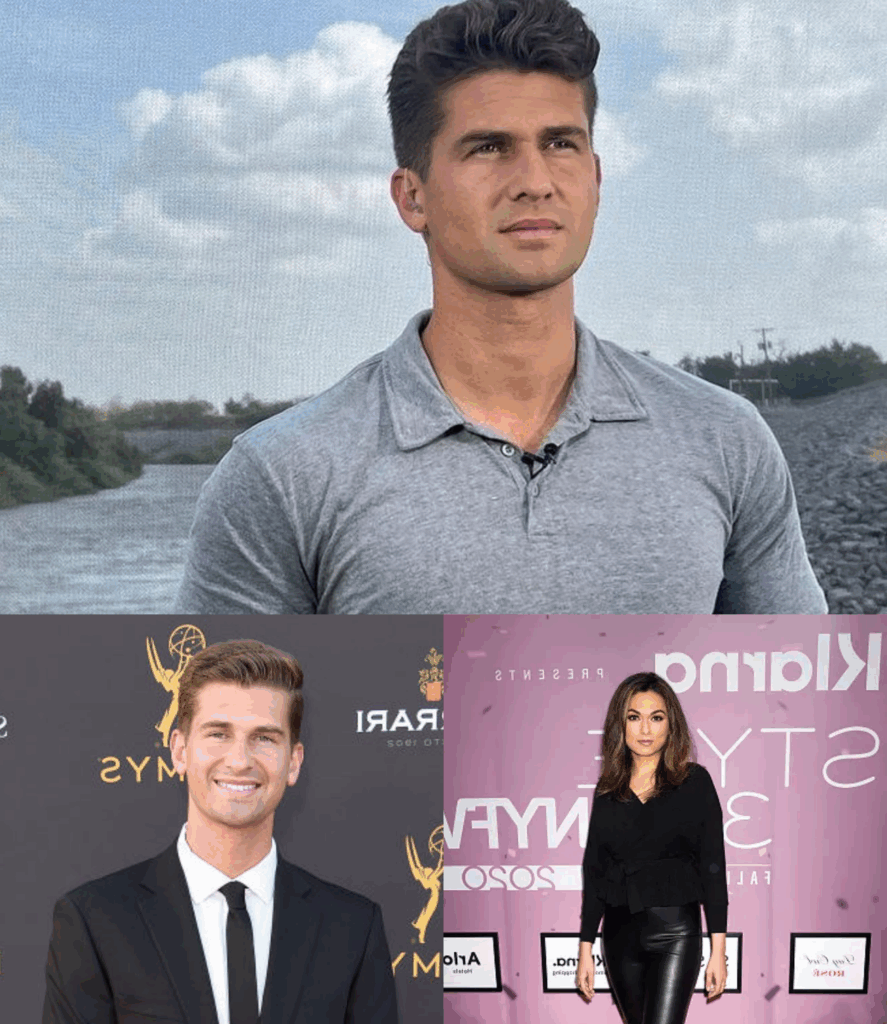

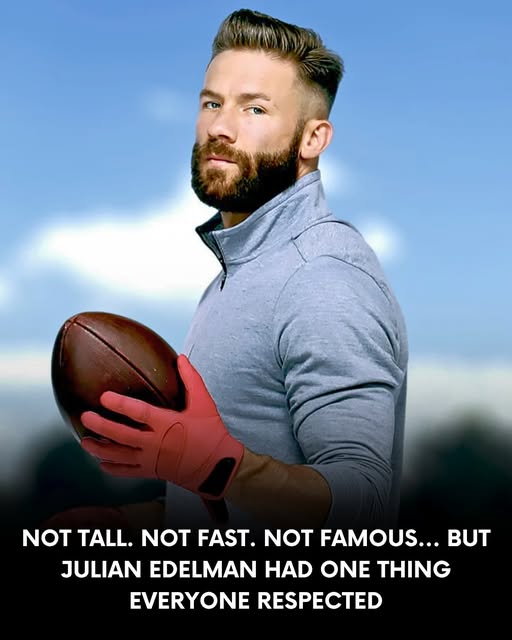

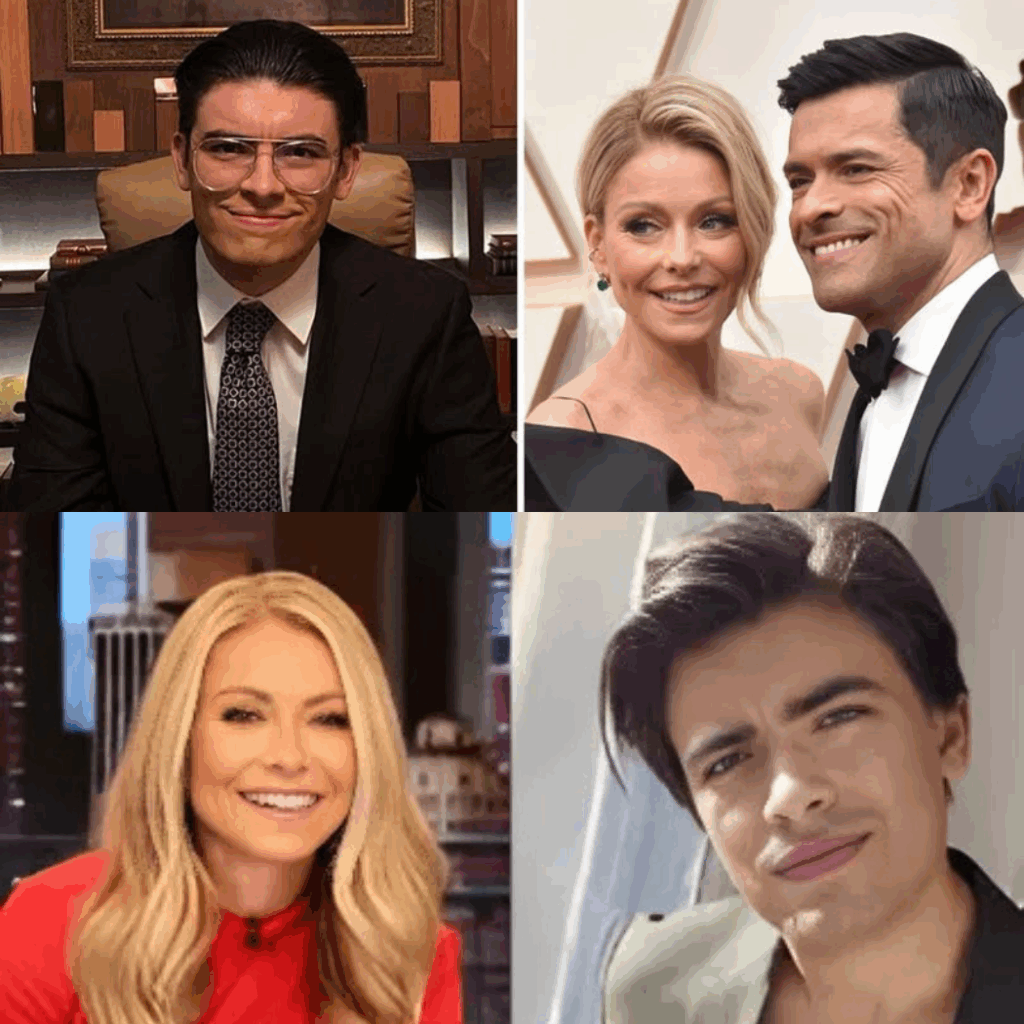

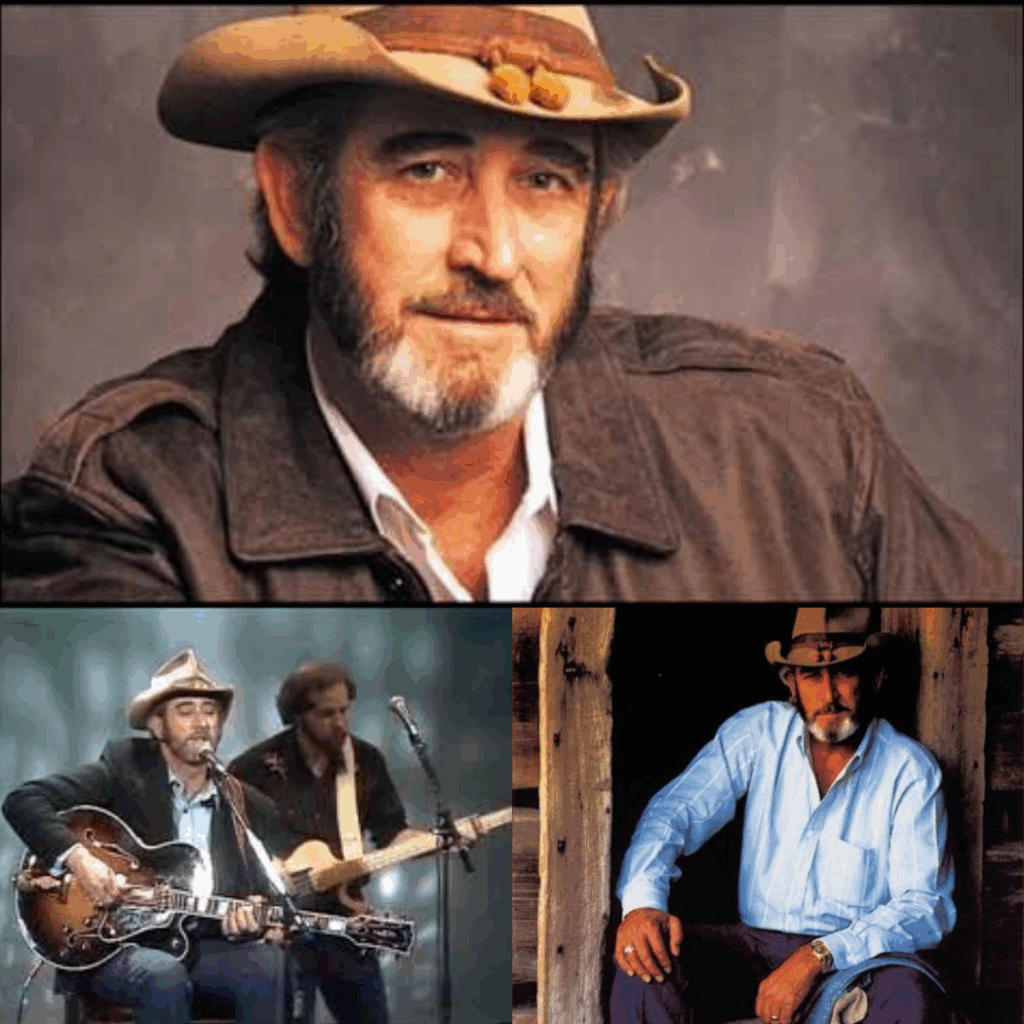

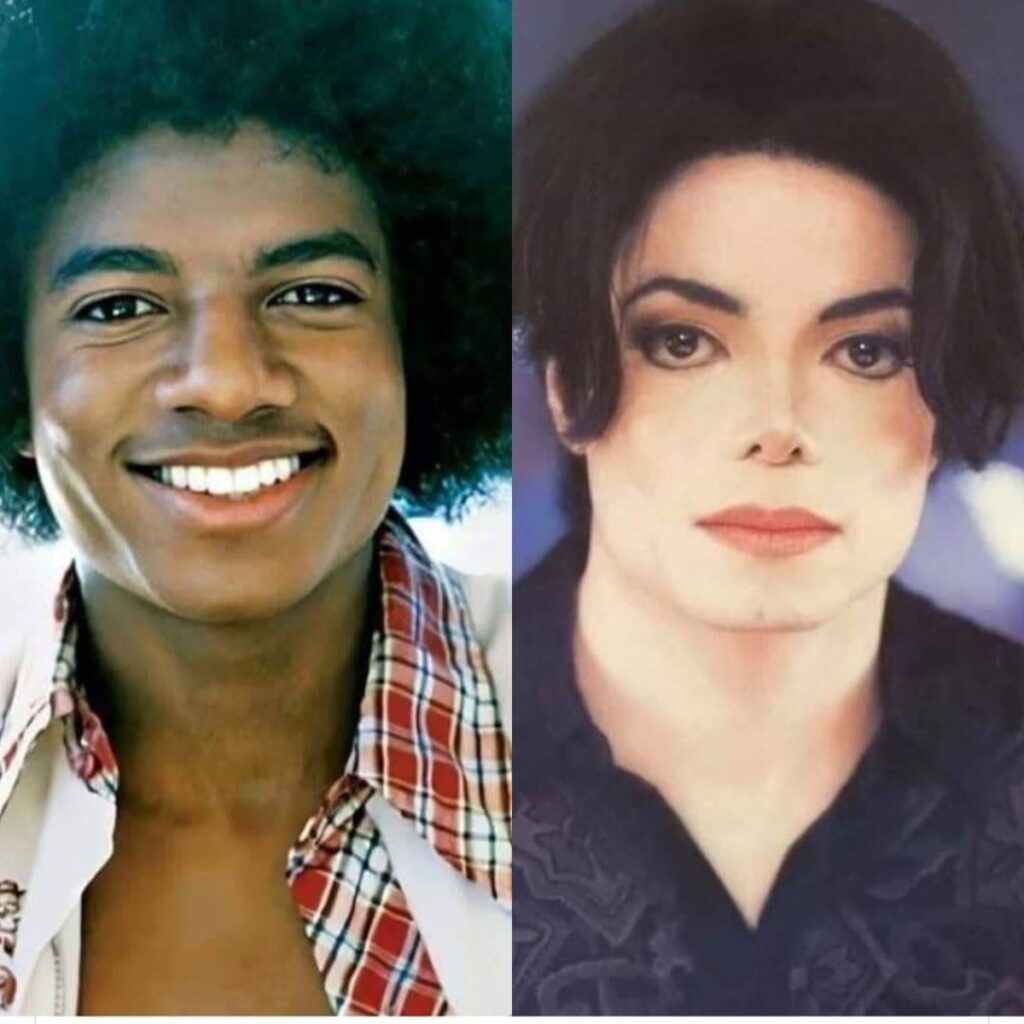

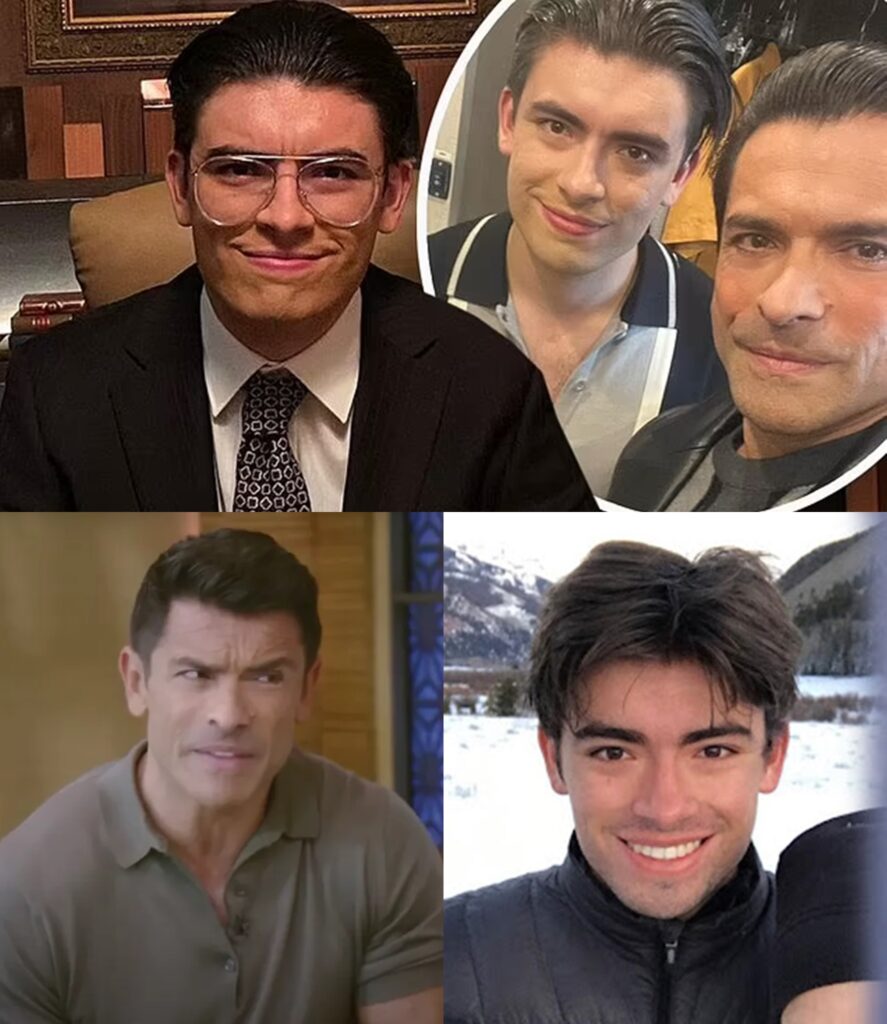

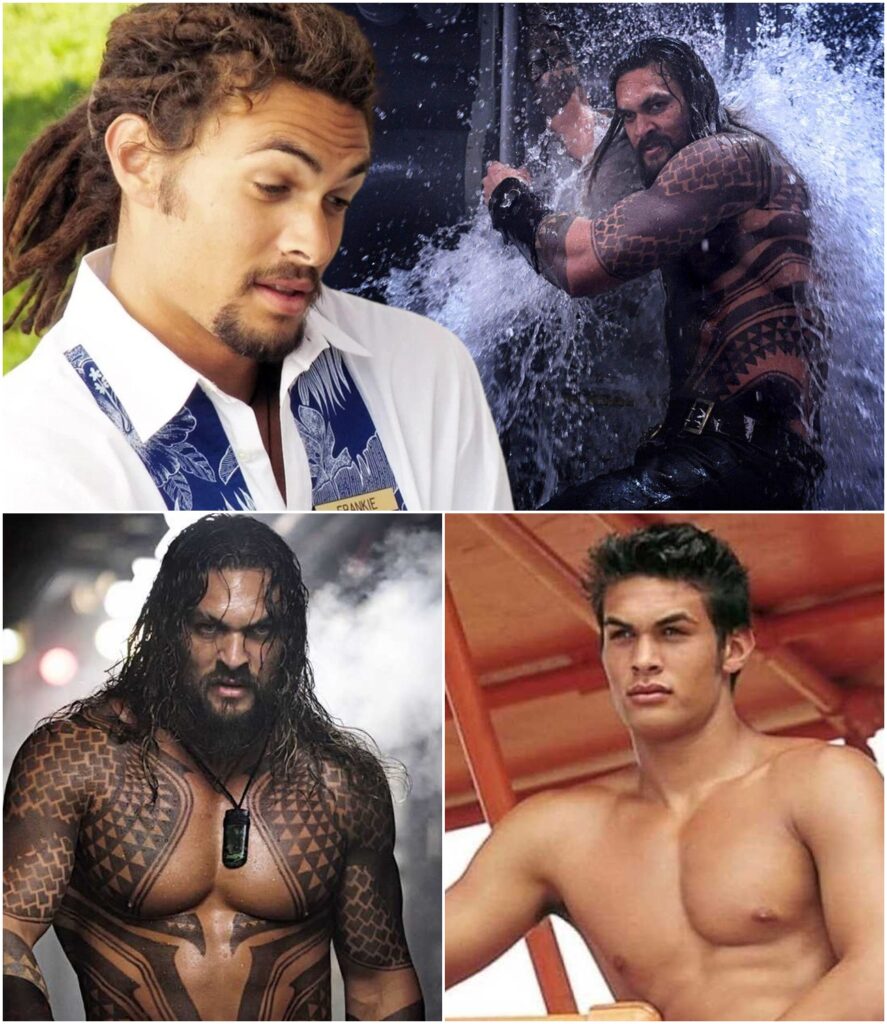

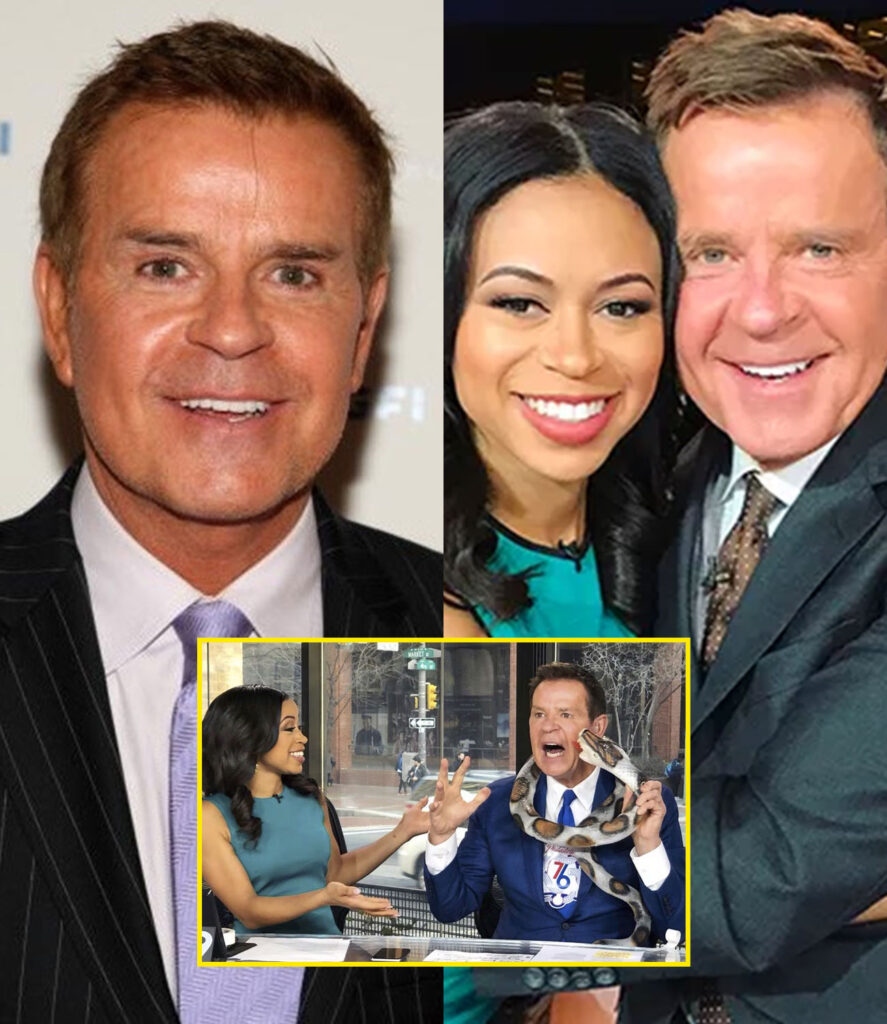

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, Sheridan moved to Los Angeles and pursued acting. He landed small roles in popular shows like Walker, Texas Ranger, Veronica Mars, and Sons of Anarchy. For a while, he was best known as Deputy Chief David Hale on Sons of Anarchy, a recurring character with a conflicted moral compass.

But acting didn’t satisfy him—and it didn’t pay well either. Sheridan found himself battling financial insecurity, taking on side jobs, and struggling to find meaning in the roles he was being offered. He often described acting as creatively stifling, saying he was “just a hired gun, reading someone else’s words.”

His breakthrough didn’t come in front of the camera—it came behind the keyboard.

The Leap into Writing

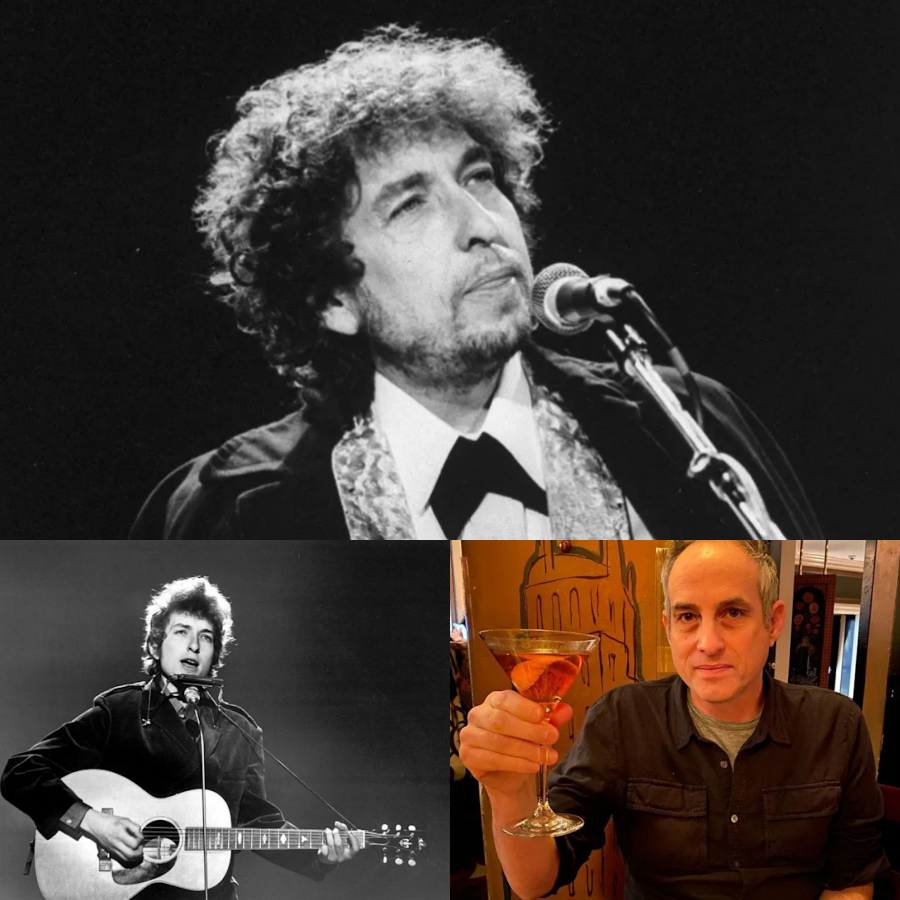

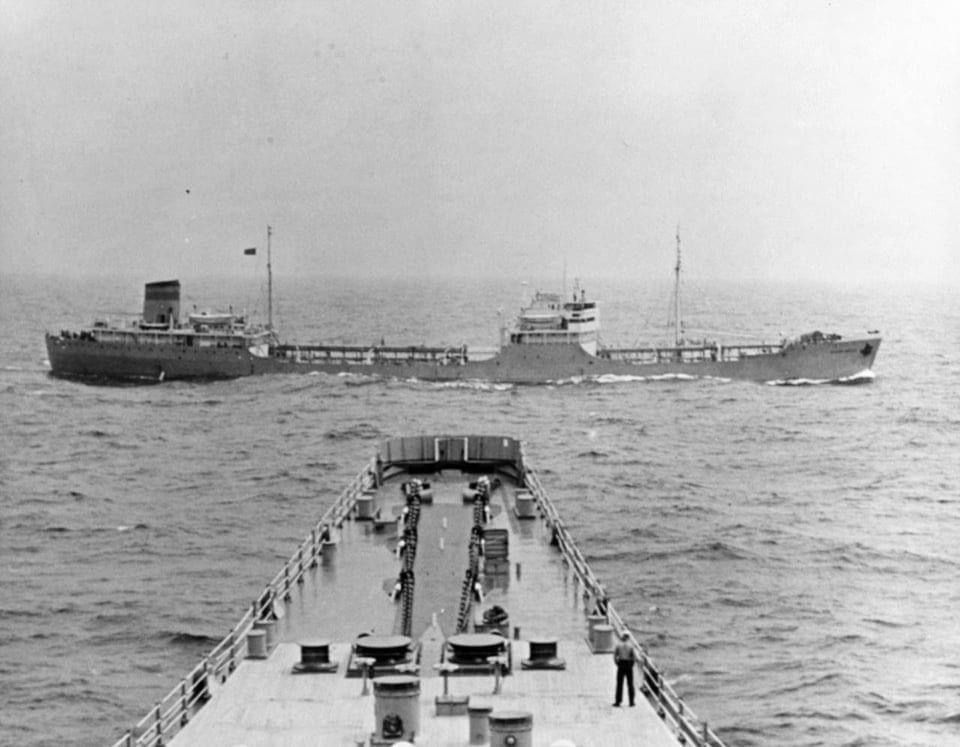

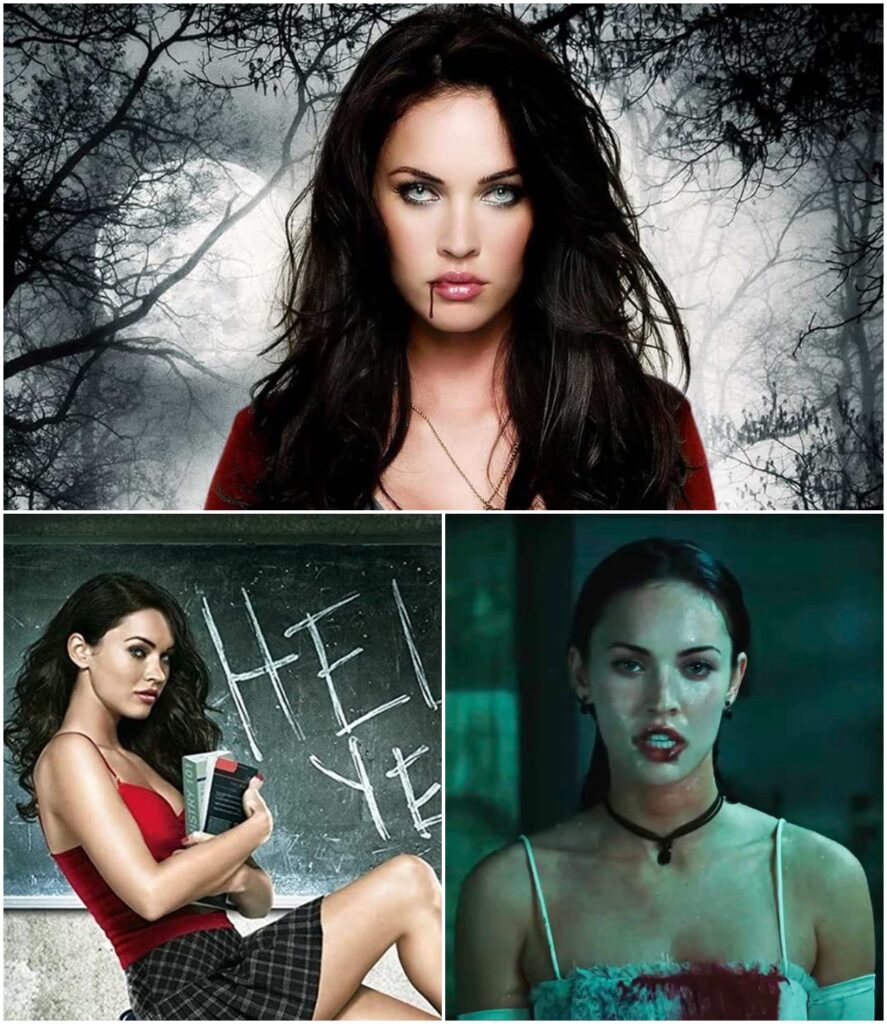

Frustrated with the Hollywood system, Sheridan taught himself how to write screenplays. His first major script, Sicario (2015), was a violent, tension-filled thriller that plunged into the murky world of the drug trade along the U.S.–Mexico border. Directed by Denis Villeneuve and starring Emily Blunt, Benicio Del Toro, and Josh Brolin, the film received critical acclaim and put Sheridan on the map as a serious screenwriter.

What made Sicario so different was Sheridan’s unapologetically raw portrayal of power, justice, and survival in an increasingly lawless world. He followed it up with Hell or High Water (2016), a modern-day Western about two brothers robbing banks to save their family ranch. That film earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Screenplay.

Suddenly, the former cowboy-turned-actor was being hailed as one of Hollywood’s freshest voices—someone who could blend gritty realism with poetic storytelling.

Yellowstone: The Empire Begins

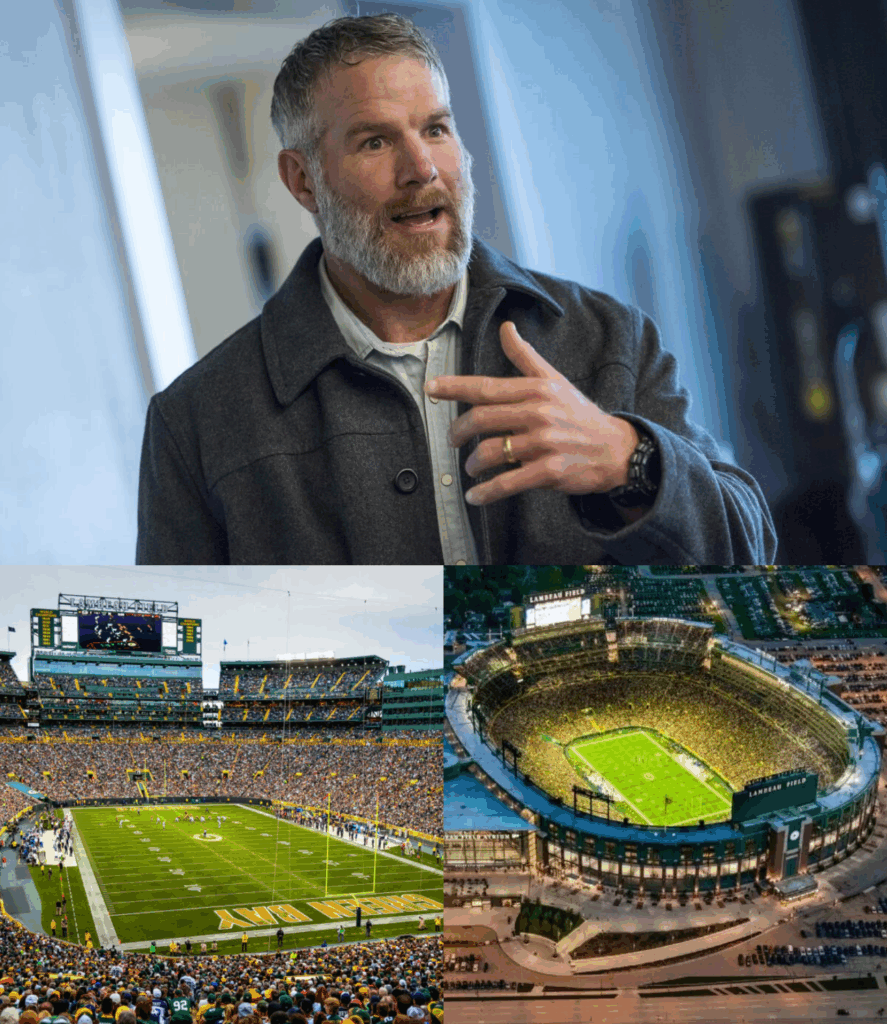

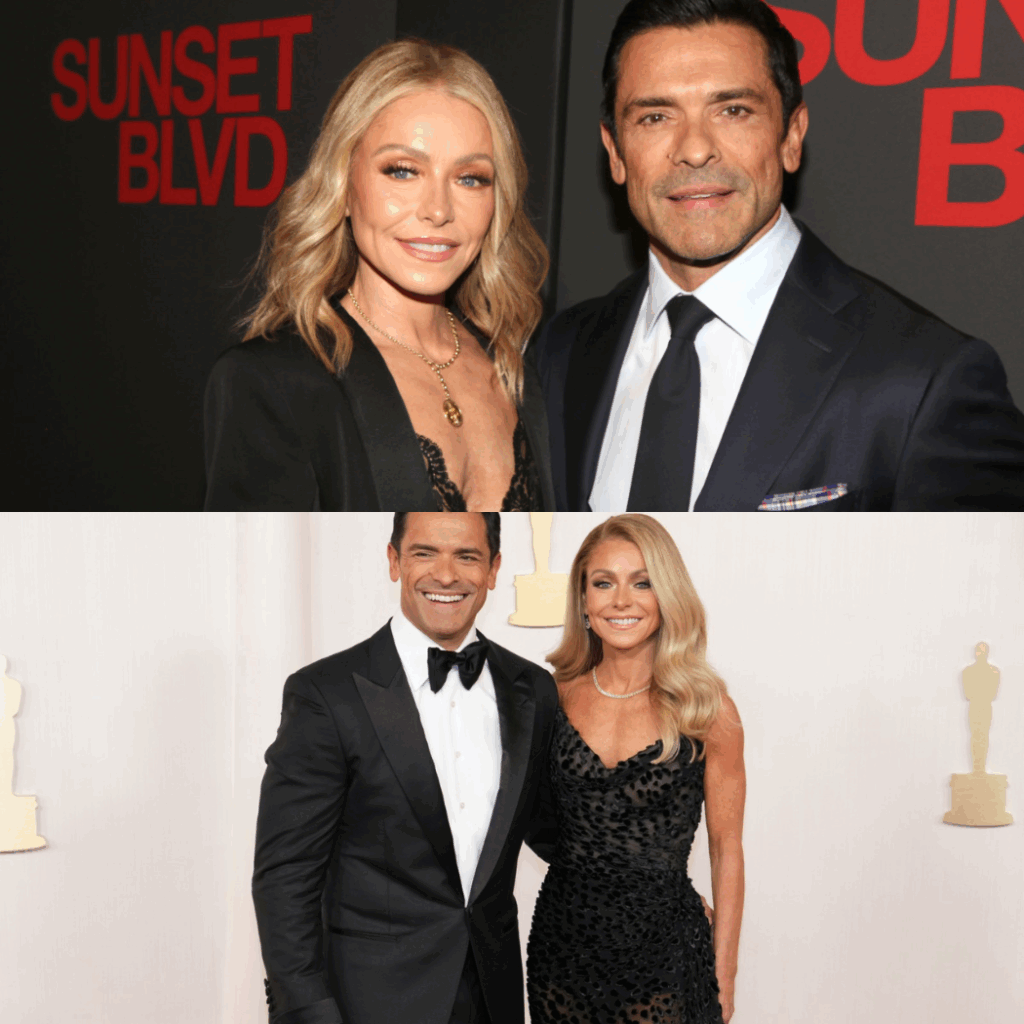

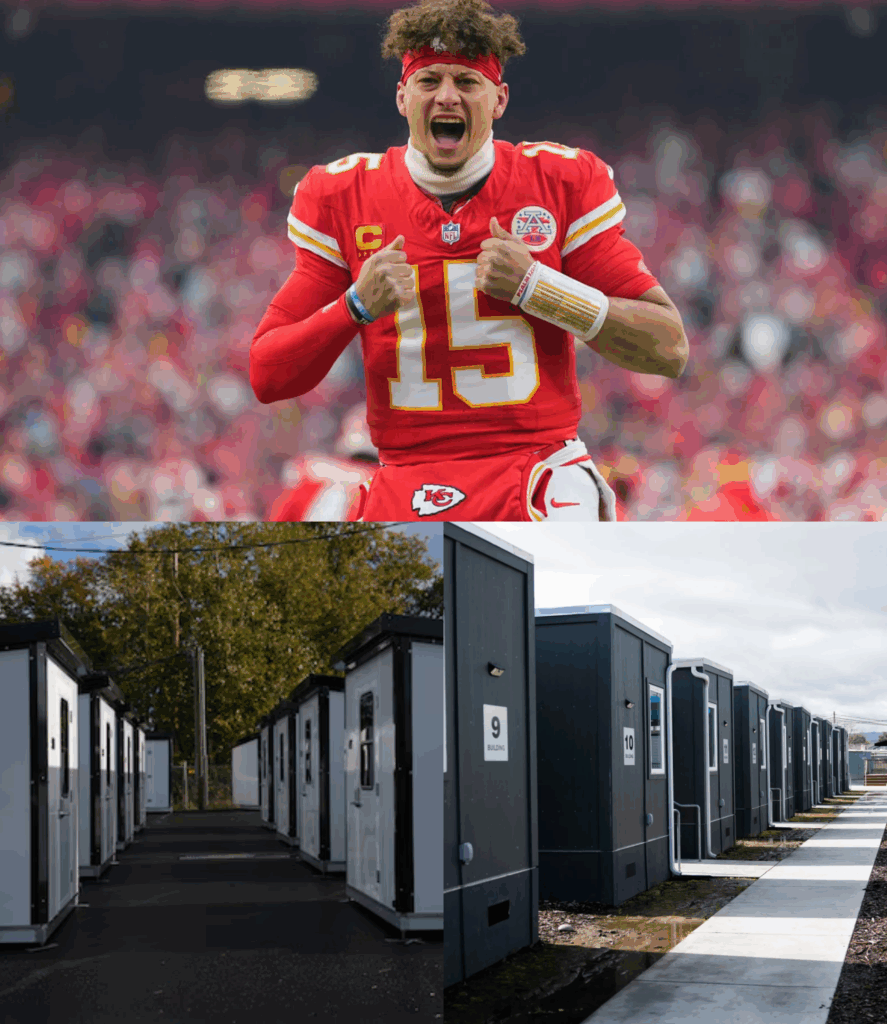

In 2018, Sheridan unleashed his greatest creation yet: Yellowstone, a drama centered on the Dutton family, powerful ranchers fighting to protect their land against developers, politicians, and Native American tribes. With Kevin Costner leading the cast and Sheridan as the showrunner and co-creator, the series became a cultural phenomenon.

What set Yellowstone apart was its ability to fuse soap opera-level family drama with sweeping, cinematic visuals and frontier justice. Viewers were hooked. By 2021, the show had become one of the most-watched programs on cable television, outperforming network giants and reshaping the idea of what modern Westerns could be.

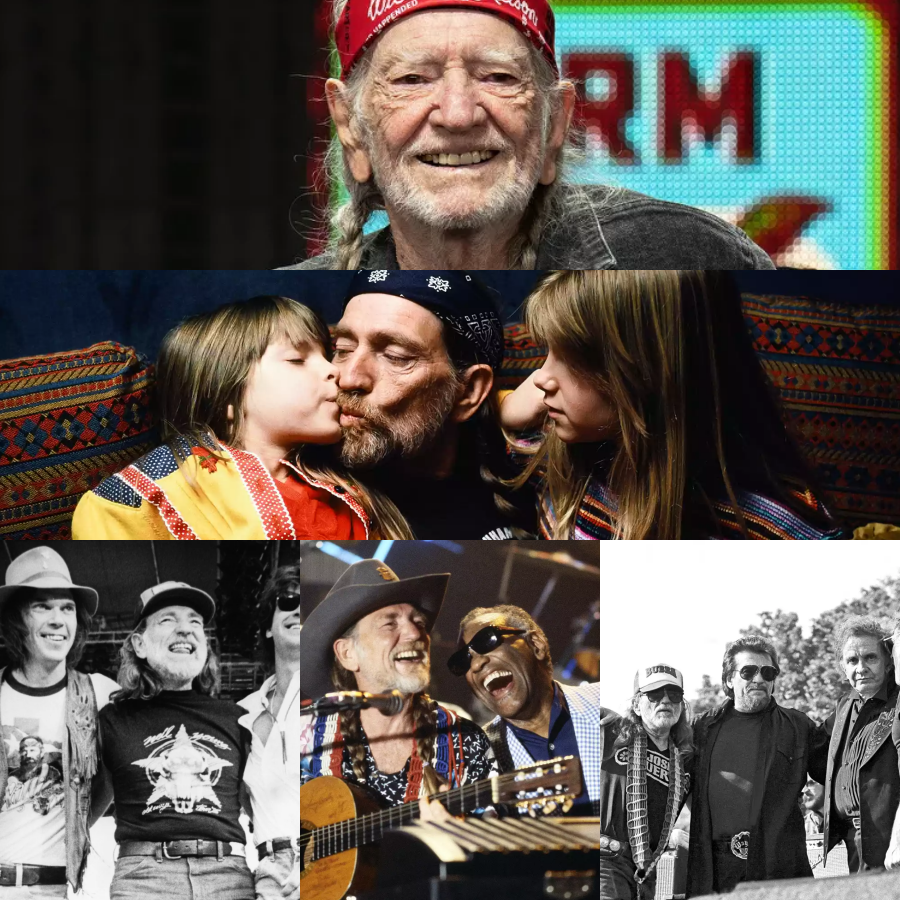

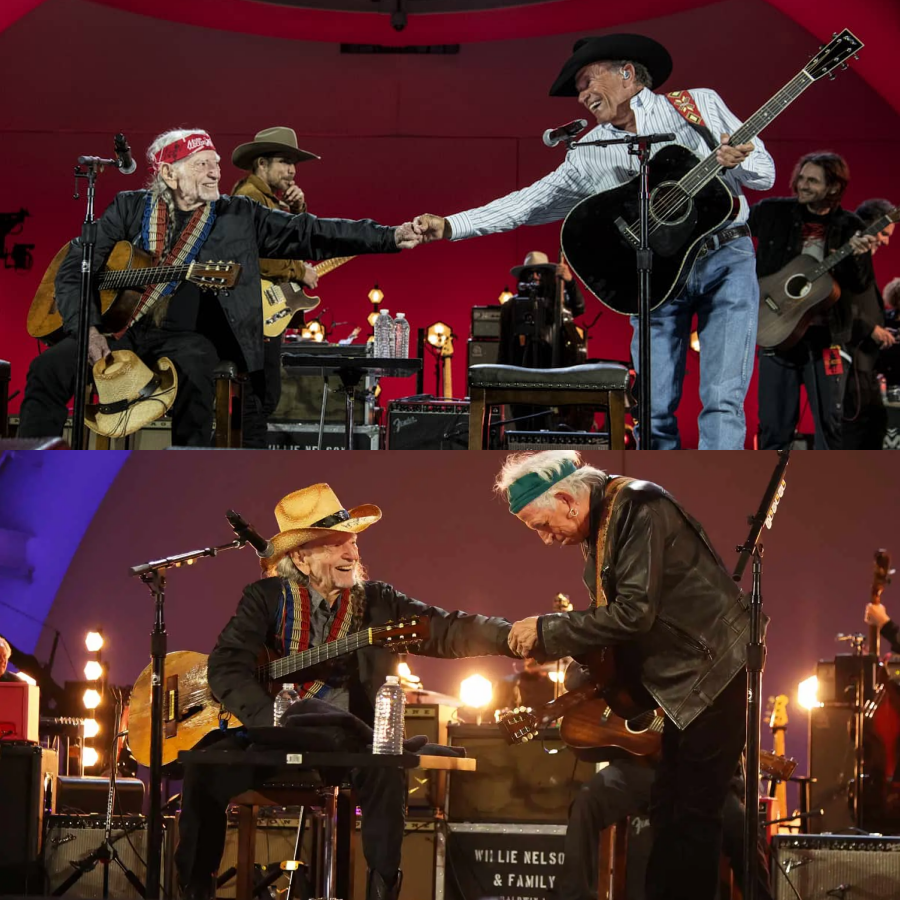

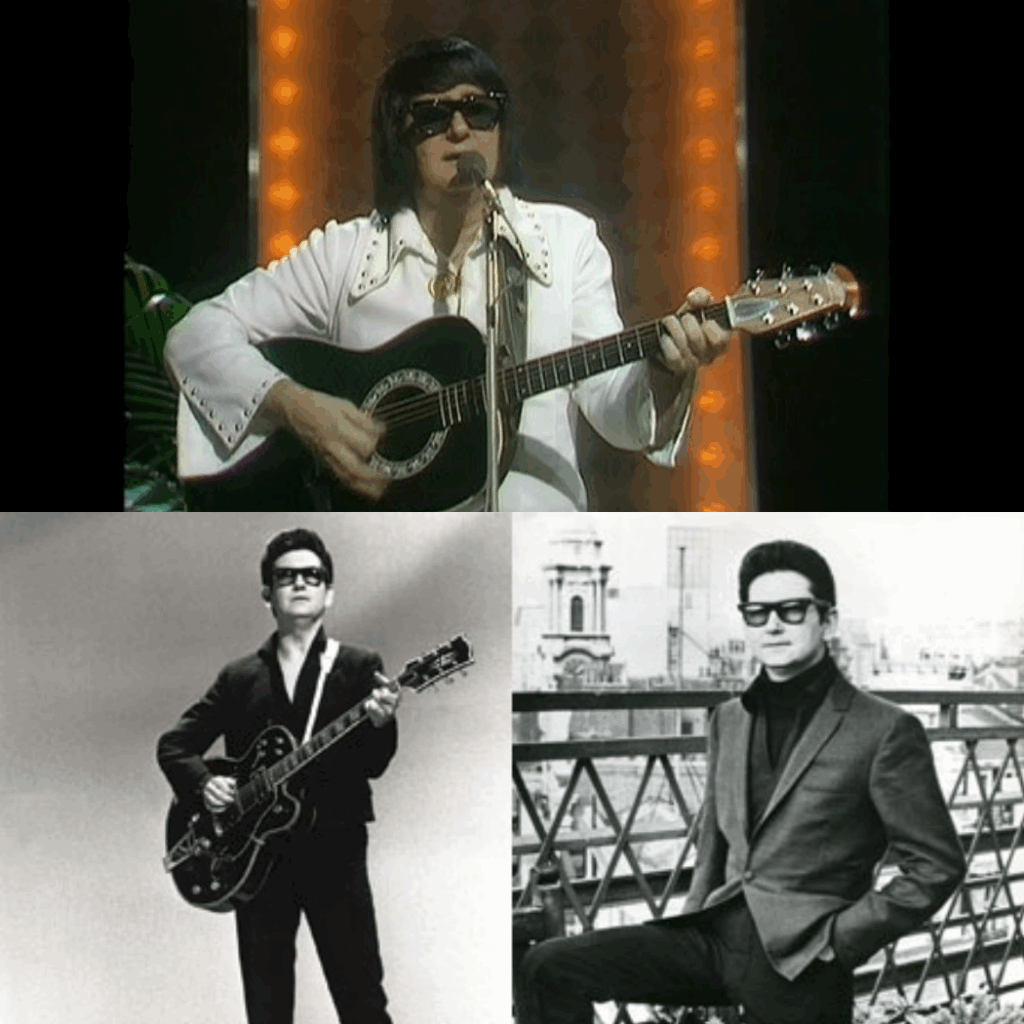

Sheridan didn’t stop there. He expanded the Yellowstone universe with prequels like 1883 (starring Tim McGraw, Faith Hill, and Sam Elliott) and 1923 (with Helen Mirren and Harrison Ford). These shows dive into the Dutton family’s generational saga, intertwining history, trauma, and survival in America’s evolving frontier.

The Sheridan TV Universe

Taylor Sheridan is not just a creator—he’s a one-man TV empire. Thanks to a lucrative deal with Paramount+, he now oversees an expanding universe of interconnected shows. Beyond the Yellowstone franchise, Sheridan created:

- Mayor of Kingstown, starring Jeremy Renner, which explores systemic corruption and prison-town politics.

- Tulsa King, a mobster drama starring Sylvester Stallone as a New York capo exiled to Oklahoma.

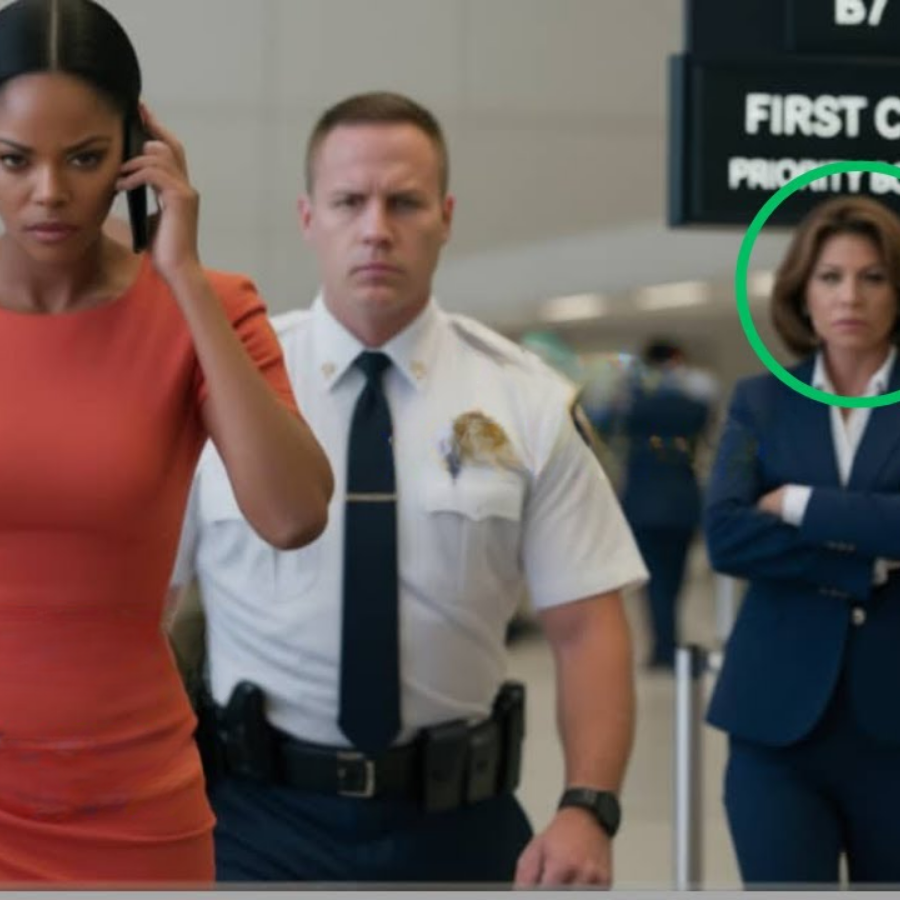

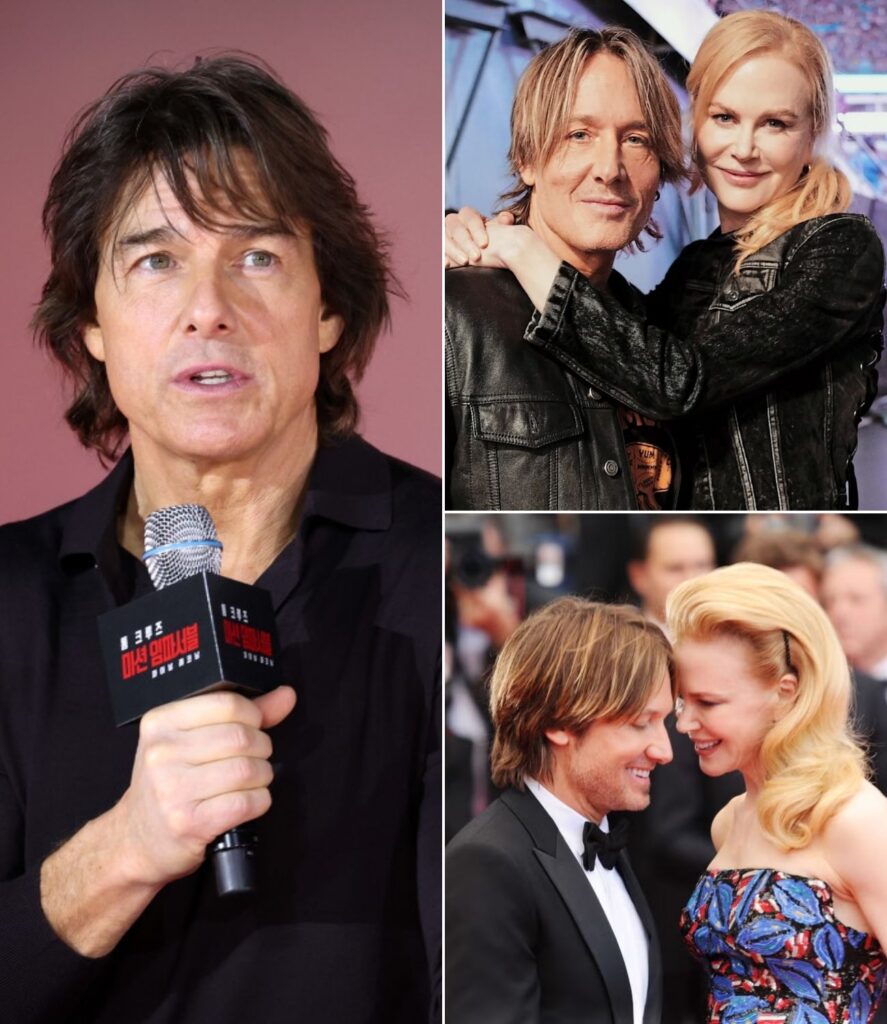

- Special Ops: Lioness, a CIA thriller led by Zoe Saldaña and Nicole Kidman.

Each show is marked by Sheridan’s signature style—gritty storytelling, morally complex characters, and a no-frills attitude toward violence and justice.

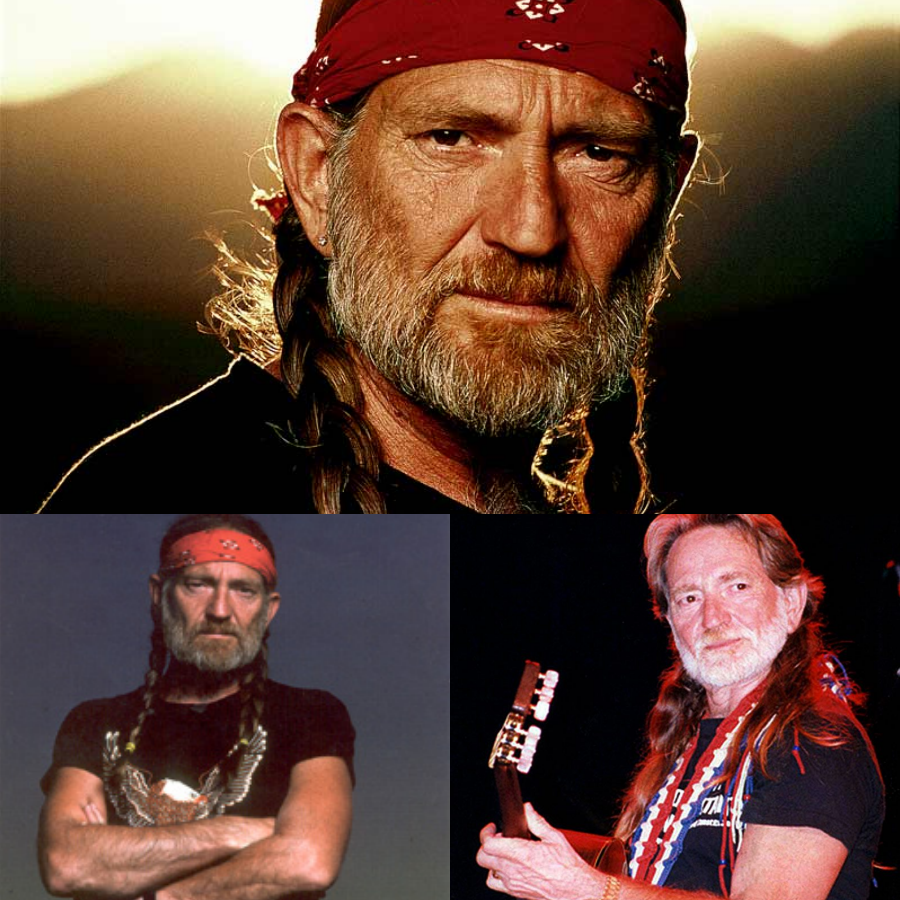

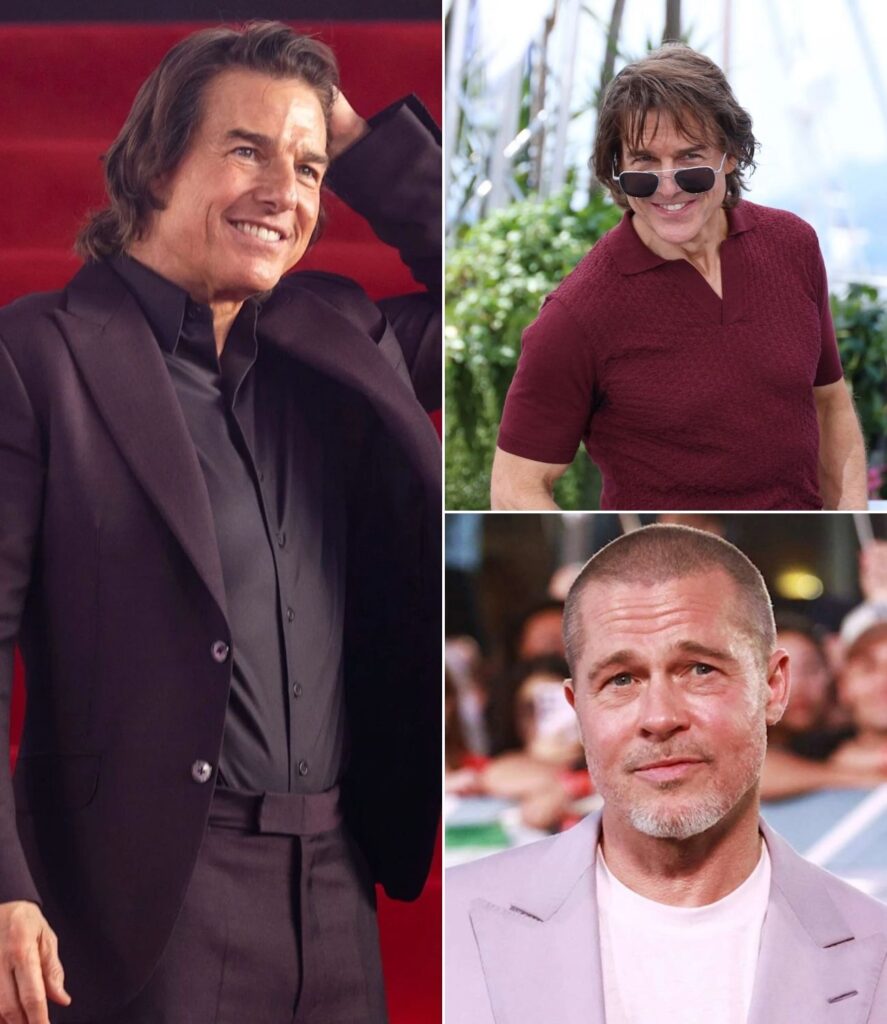

The Real-Life Cowboy

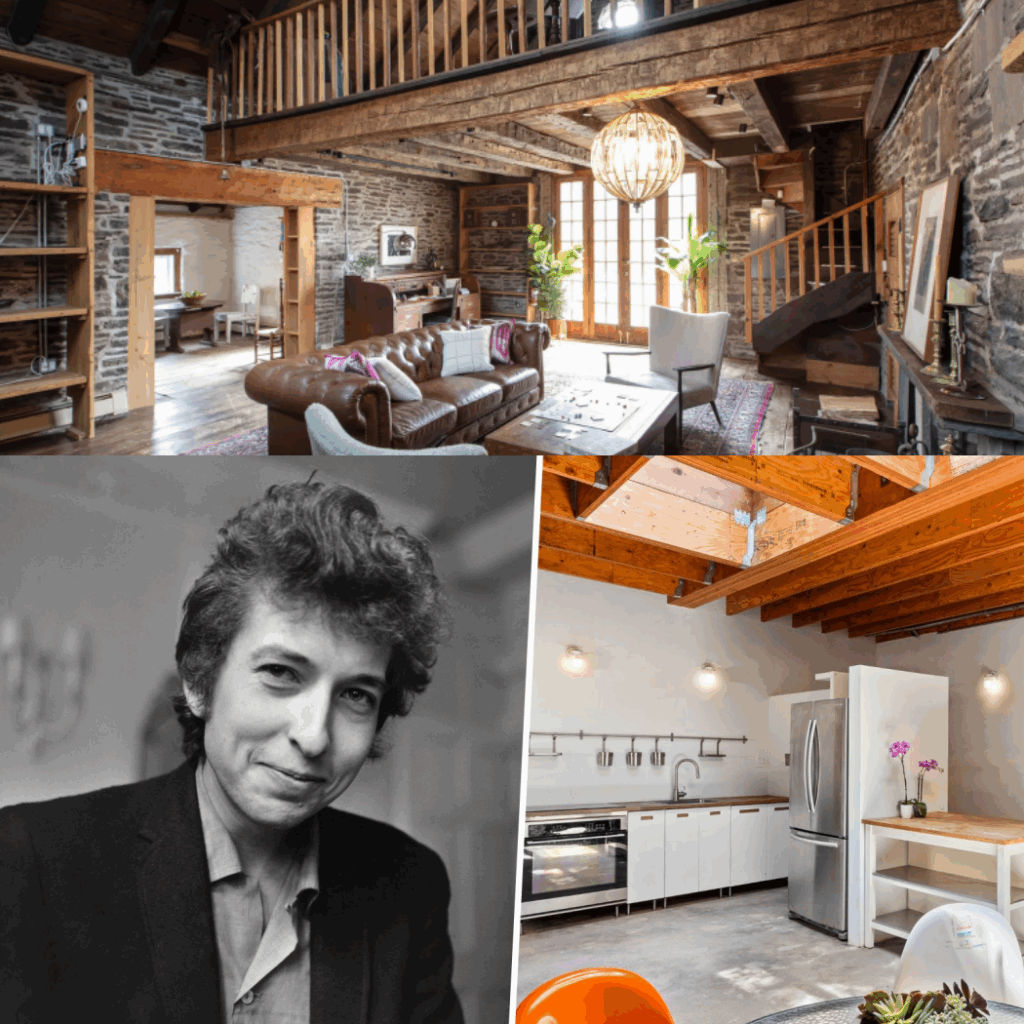

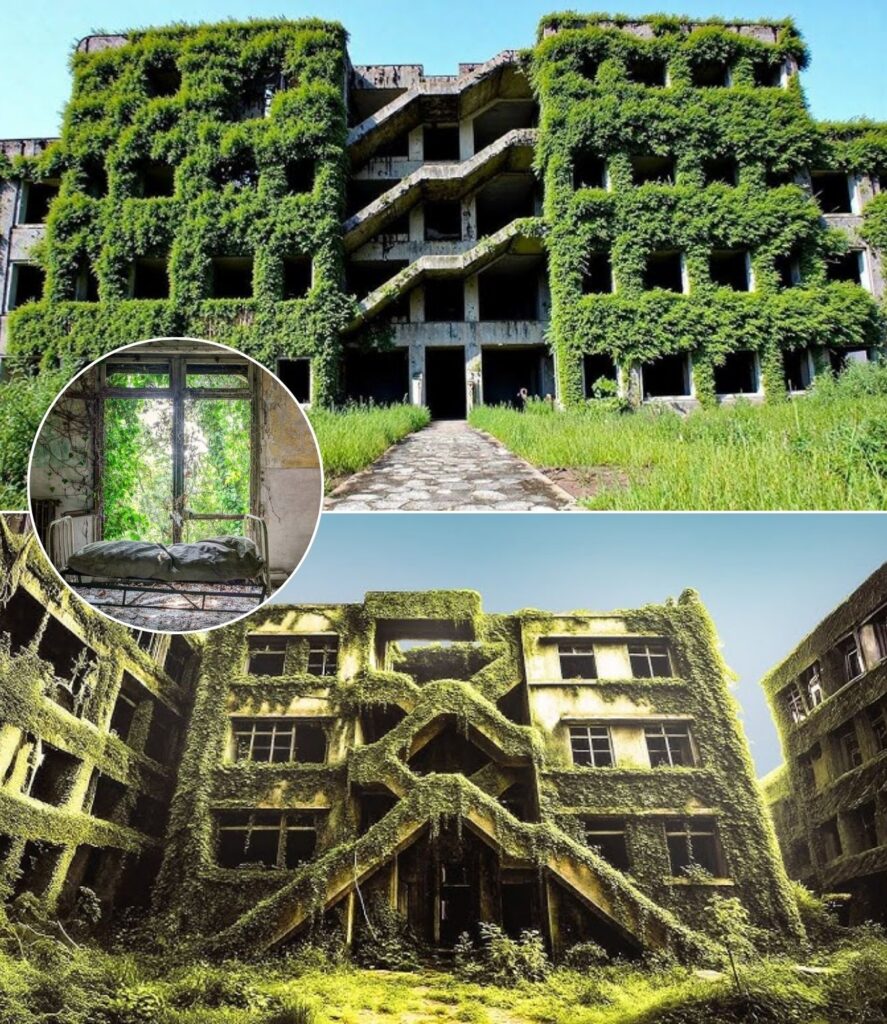

Despite his Hollywood success, Sheridan never left his roots behind. He lives on a sprawling ranch in Weatherford, Texas, where he trains horses and oversees the Bosque Ranch, a working cowboy facility and event space. He’s also an active competitor in reining competitions, a sport where riders guide horses through precise maneuvers at high speed.

Sheridan doesn’t just write about cowboys—he is one.

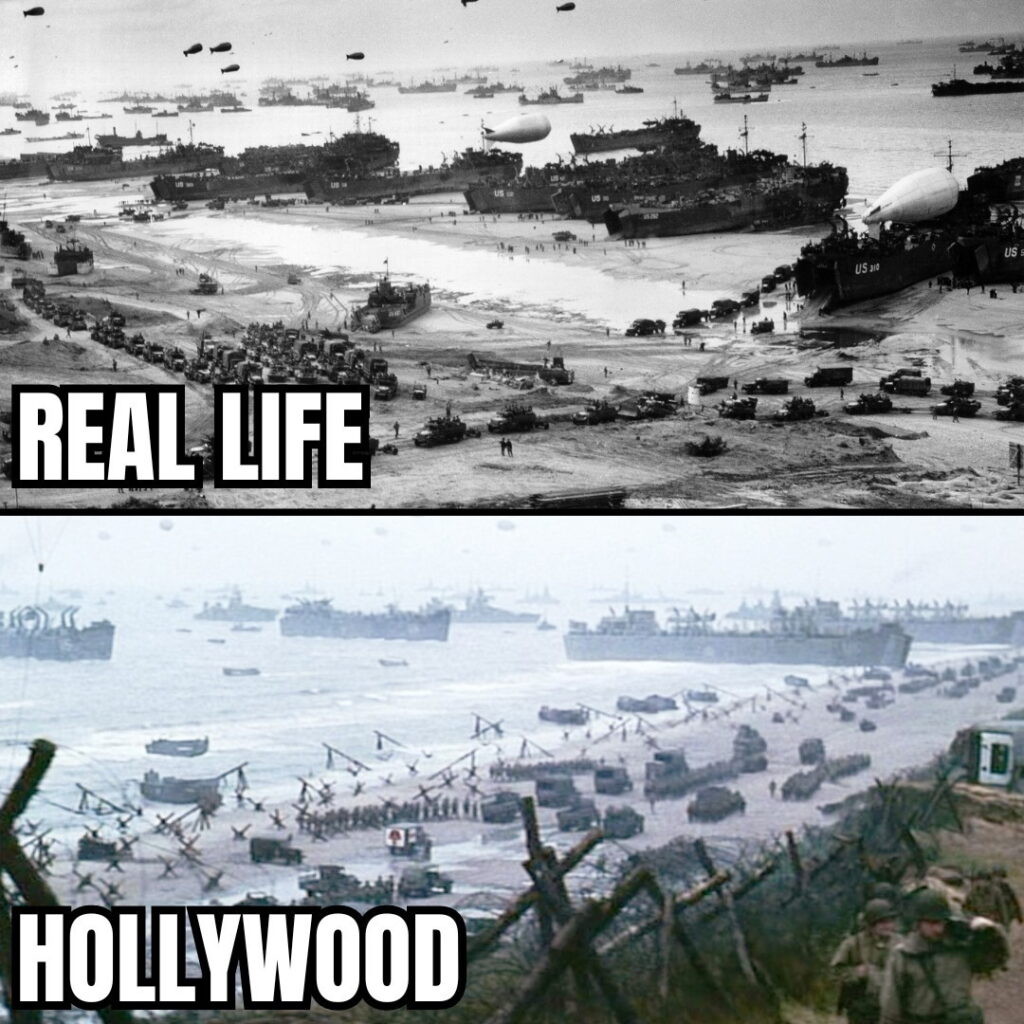

He’s been open about the importance of preserving cowboy culture and rural traditions. He employs real cowboys in his productions, often casting non-actors in supporting roles. Even Yellowstone has scenes shot with real horse wranglers, ranchers, and rodeo athletes. Authenticity is key in Sheridan’s world.

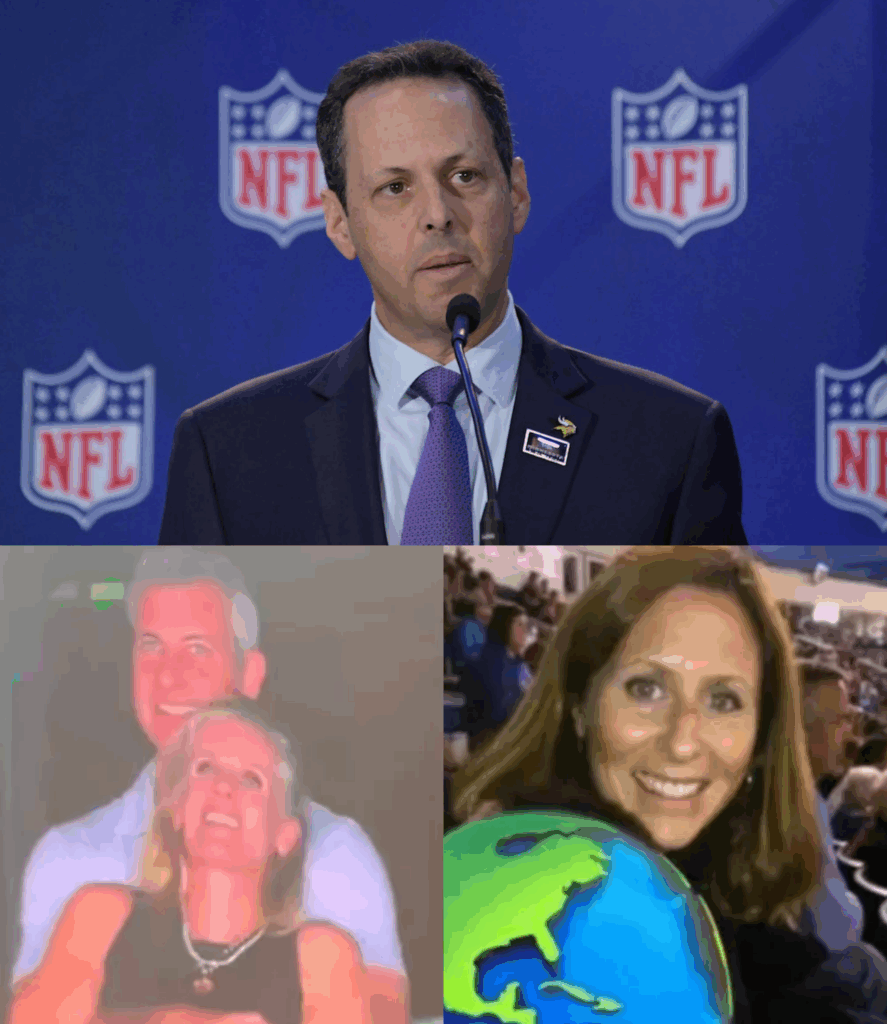

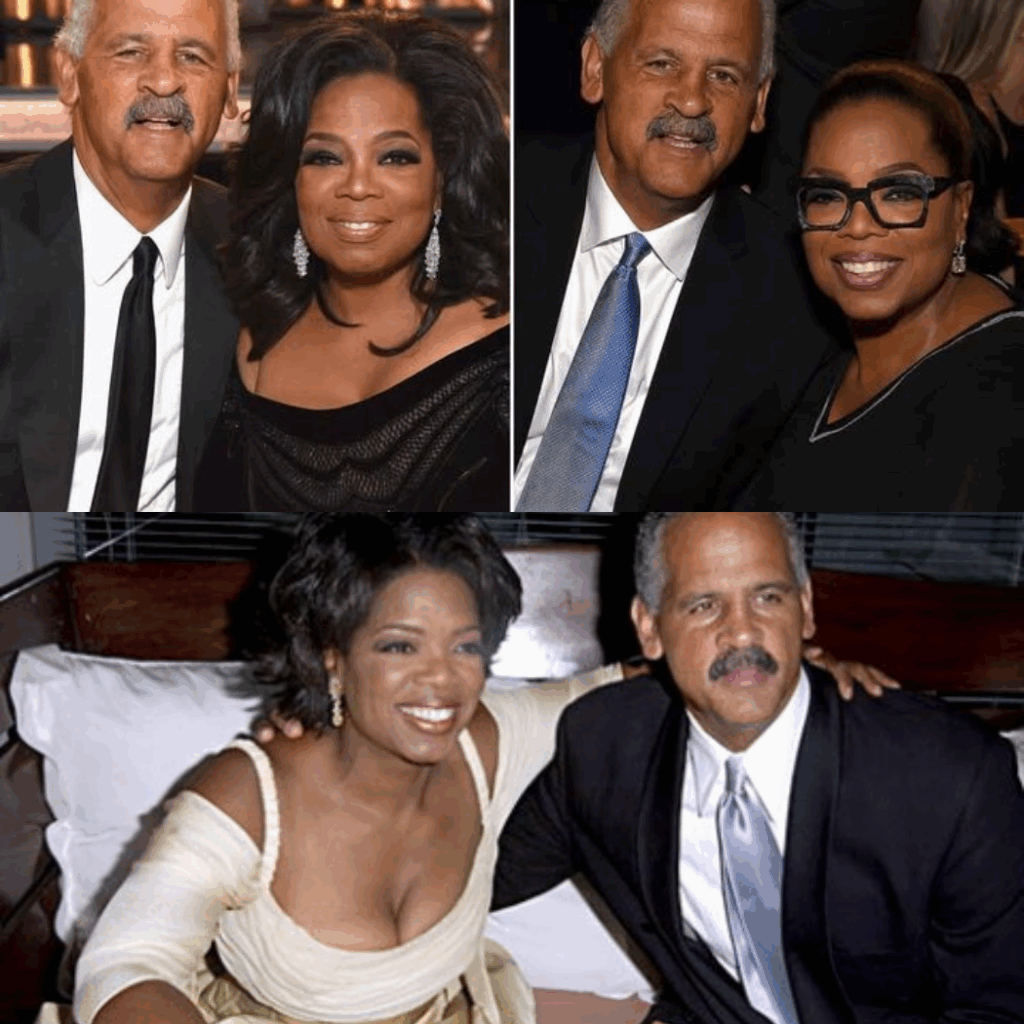

Glasser had seen the potential in the Yellowstone script, and in Sheridan, who had left behind his career as a character actor to write full-time. He’d helped Sheridan pry the show from HBO – taking Yellowstone to potential alternative suitors, from whom he’d received a series of polite, and not so polite, passes. Still, he had pressed on.

Finally, Glasser had attracted some interest. Viacom was preparing to launch a new cable channel, the Paramount Network, and it needed original shows. The executives wanted Yellowstone.

Sheridan, however, was threatening to derail the whole thing. When Glasser had asked him to come to Hollywood for the pitch meeting, the screenwriter had at first refused to leave his home in Park City, Utah. To coax him into attending the meeting, Glasser had to fly him there by private jet and promise him that he wouldn’t have to spend the night in LA, a city Sheridan had come to hate. Glasser had finally got Sheridan in a room with Viacom executives. But what Sheridan delivered was less a pitch than a warning.

You will have no part in any of this, he told them – except for footing the bill. I will write and direct all the episodes of the show. There will be no writers’ room. There will be no notes from studio executives. No one will see an outline.

“It’s going to cost $US90 million to $US100 million,” he says he told them. “You’re going to be writing a cheque for horses that’s $US50,000 to $US75,000 a week.” You really want to do this?

They were crazy to accept Sheridan’s terms. But they were impressed by the cut Glasser had shown them of Wind River – the third film Sheridan had written about the contemporary American frontier, following Sicario (2015) and Hell or High Water (2016), and the first he had directed.

And they liked the fact that Kevin Costner had signed on to play Yellowstone’s lead character, John Dutton.

A fundamental thing

Dutton is watching his way of life slip away, his family along with it, and he is willing to do anything to hold on to both, no matter how bloody the cost. (A lot of people get murdered in Yellowstone.)

“This was one of the fundamental things I wanted to look at: when you have a kingdom, and you are the king, is there such a thing as morality?” Sheridan tells me.

“Because anyone trying to take your kingdom and remove you as king is going to replace your morality for theirs. So, does morality factor into the defence of the kingdom? And what does that make the king? And at the end of the day, that’s really what the show is about.”

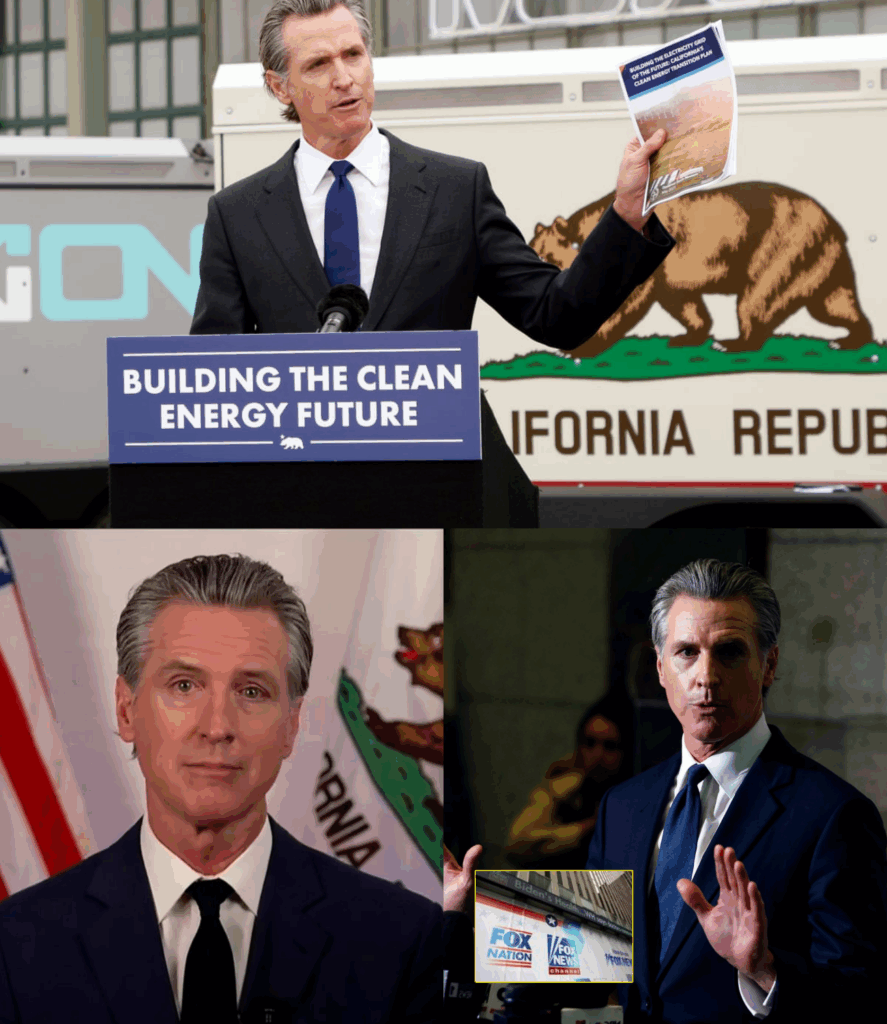

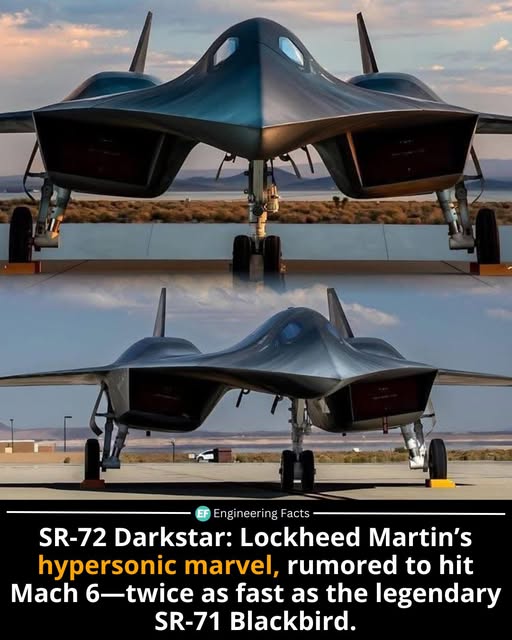

Sheridan knows something about kingdoms. At 52, he is now the heavy-handed sovereign of perhaps the most important one on television. The latest season of Yellowstone was the most-watched show on television last year, besides NFL football. He helped Paramount’s new streaming service, Paramount+, gain millions of new subscribers with multiple spin-offs of Yellowstone. A prequel, 1883, came out late last year, and will soon be followed by two more: 1923, which will launch in December, as well as Bass Reeves, which is slated for next year. Another Yellowstone spin-off is also scheduled to premiere next year – 6666, set at the legendary Four Sixes Ranch.

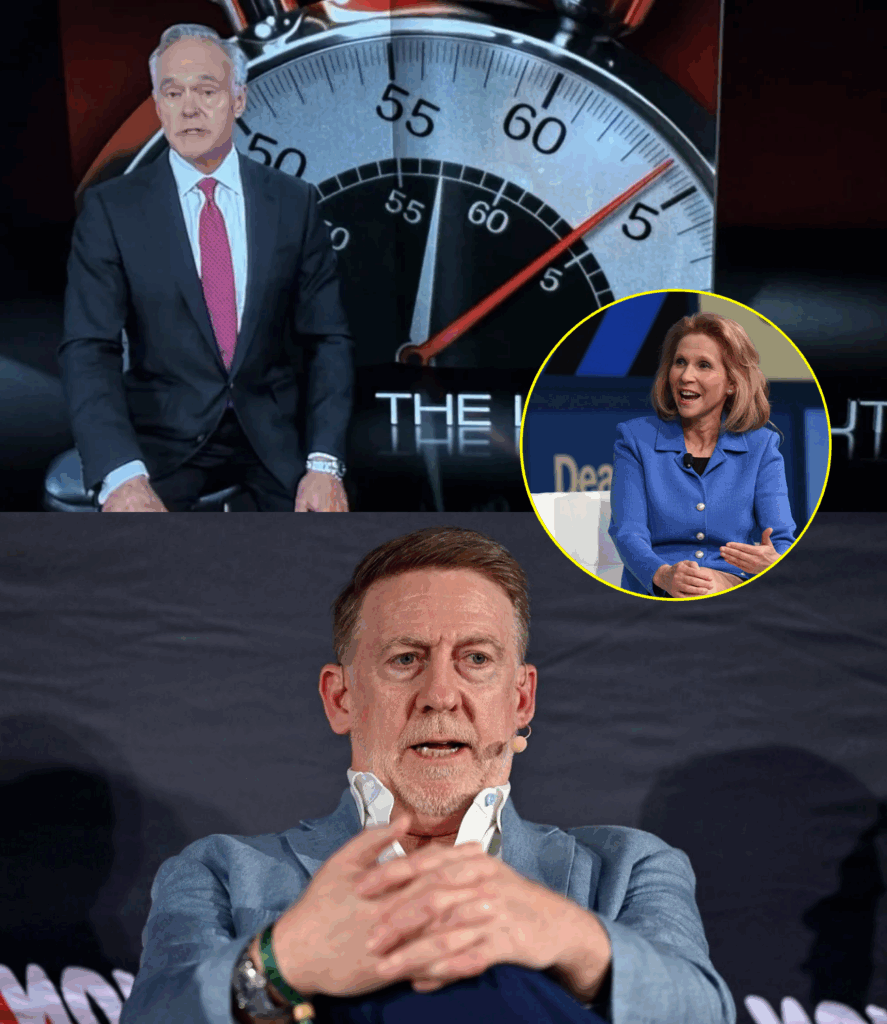

“He is, by far, the most important creator right now, arguably at any network,” Matthew Belloni, a founding partner of media and politics website Puck, tells me.

Formidable skills

Four years after Yellowstone’s debut, Sheridan is now in a league with such creators as Shonda Rhimes (Grey’s Anatomy, Scandal) and Dick Wolf (Law & Order).

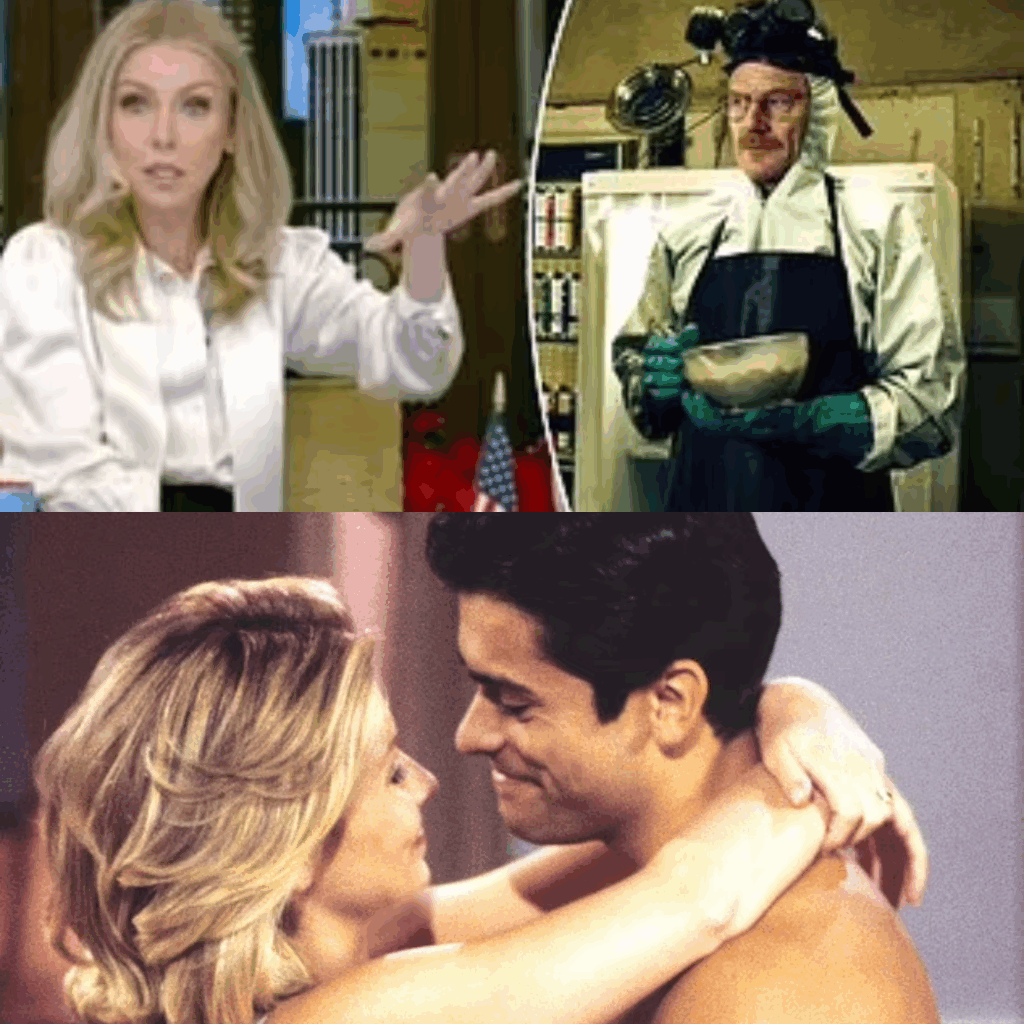

Only Sheridan might have the more arduous workload. “Most of the writer-producers at his level are essentially managers of a machine. He is actually writing a great deal of this output, which is unbelievable to me,” Belloni says. Even the most exacting of Peak TV’s auteurs – David Chase (creator of The Sopranos), Vince Gilligan (Breaking Bad ), Matthew Weiner (Mad Men) – didn’t insist on writing every episode themselves.

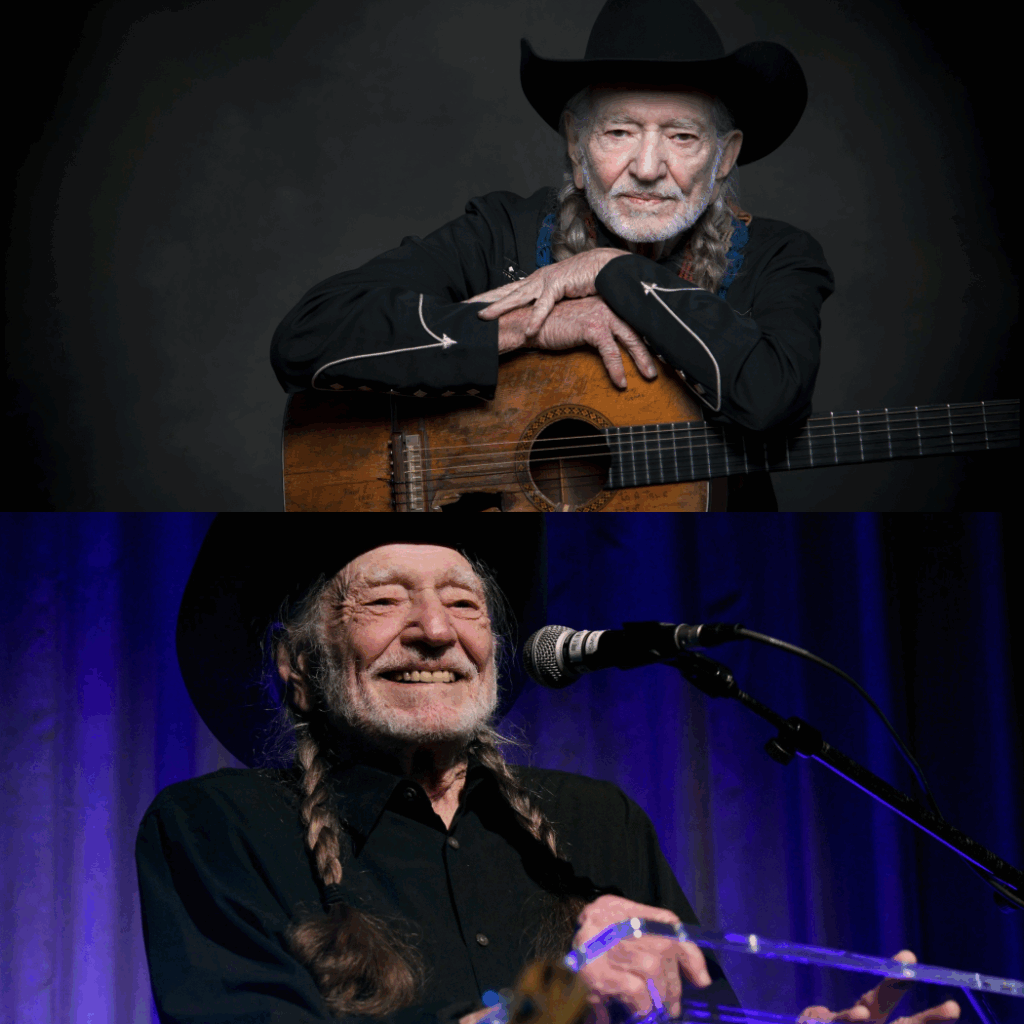

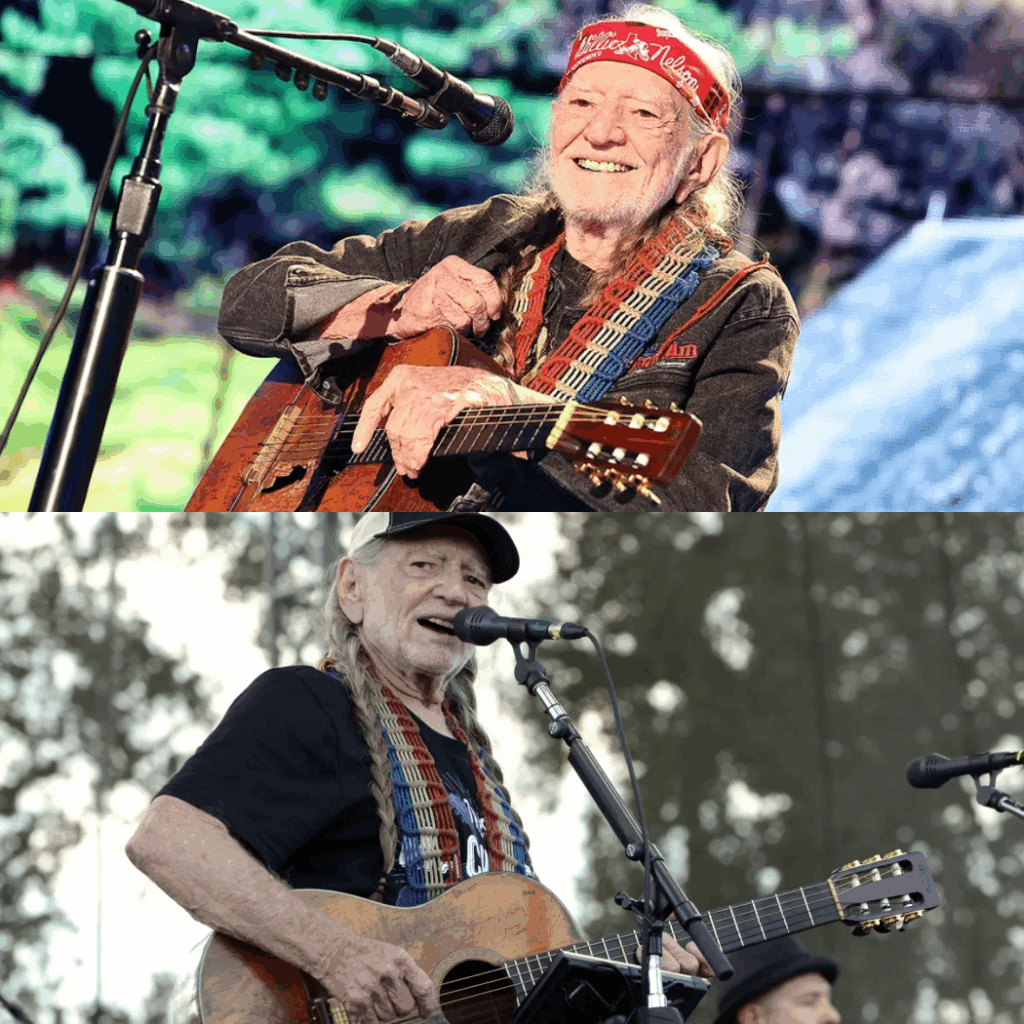

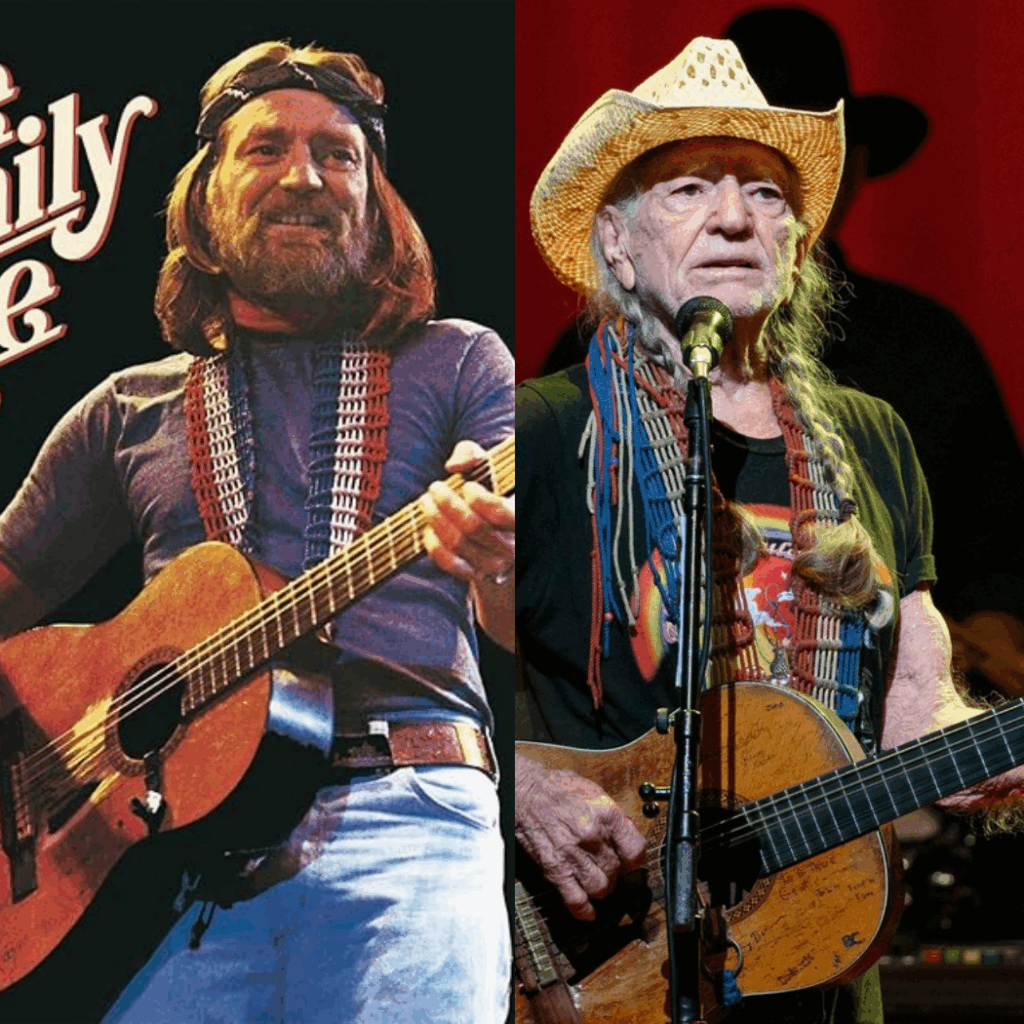

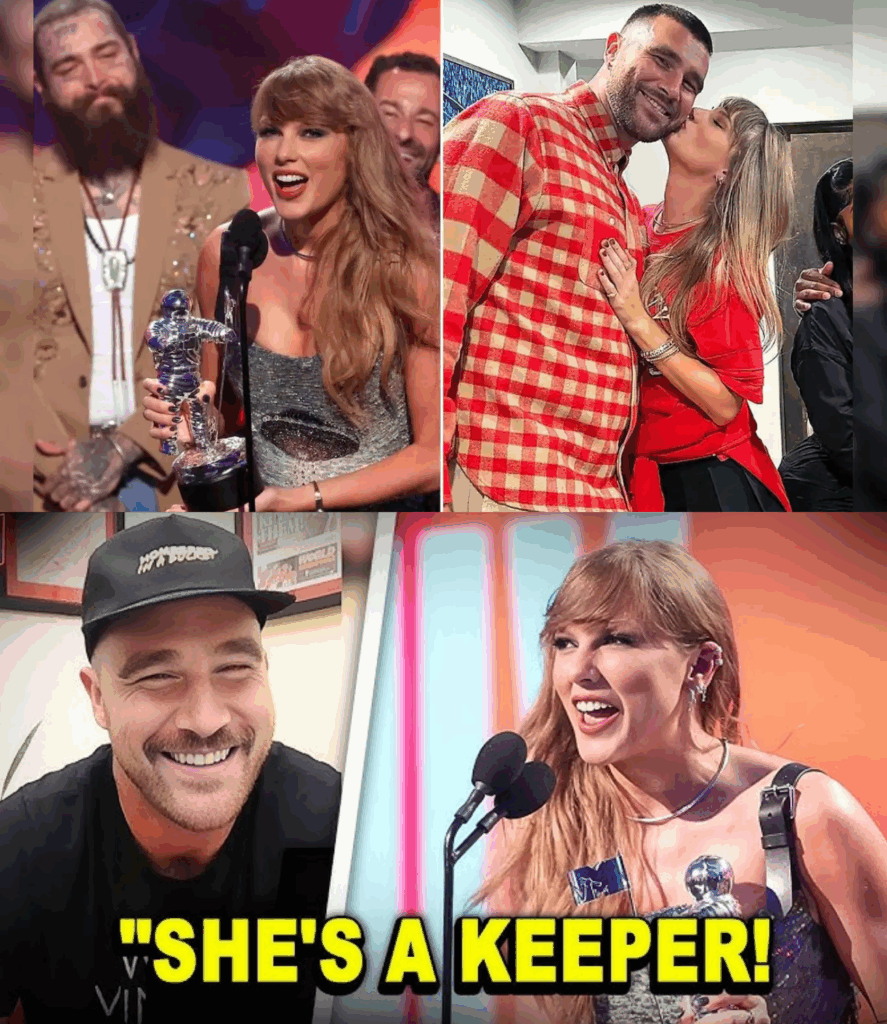

Sheridan does all of this writing, by the way, while also playing a recurring character on Yellowstone : Travis Wheatley, a high-end horse trader and a rodeo performer. The role enables him to show off his formidable cowboying skills.

For all of his evident success, Sheridan and the universe he’s created occupy a peculiar place on the American cultural landscape. Despite its high ratings, and Paramount’s explicit attempts to position it as prestige television, the series doesn’t get critical love, or even much critical attention.

In January last year, when the show received a major nomination (for best ensemble in a drama series) from the Screen Actors Guild, some thought the show’s breakthrough critical moment might finally have arrived. But when the Emmy finalists were announced, Yellowstone was shut out.

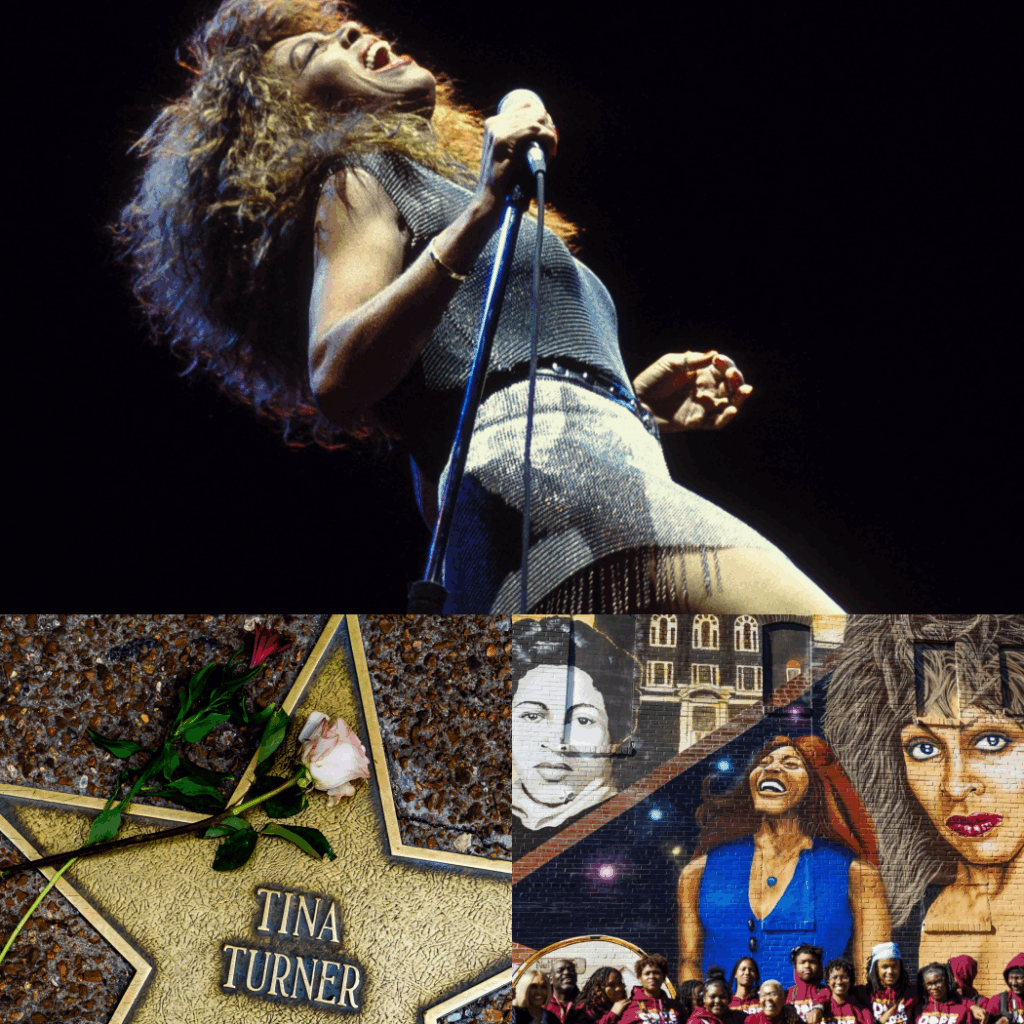

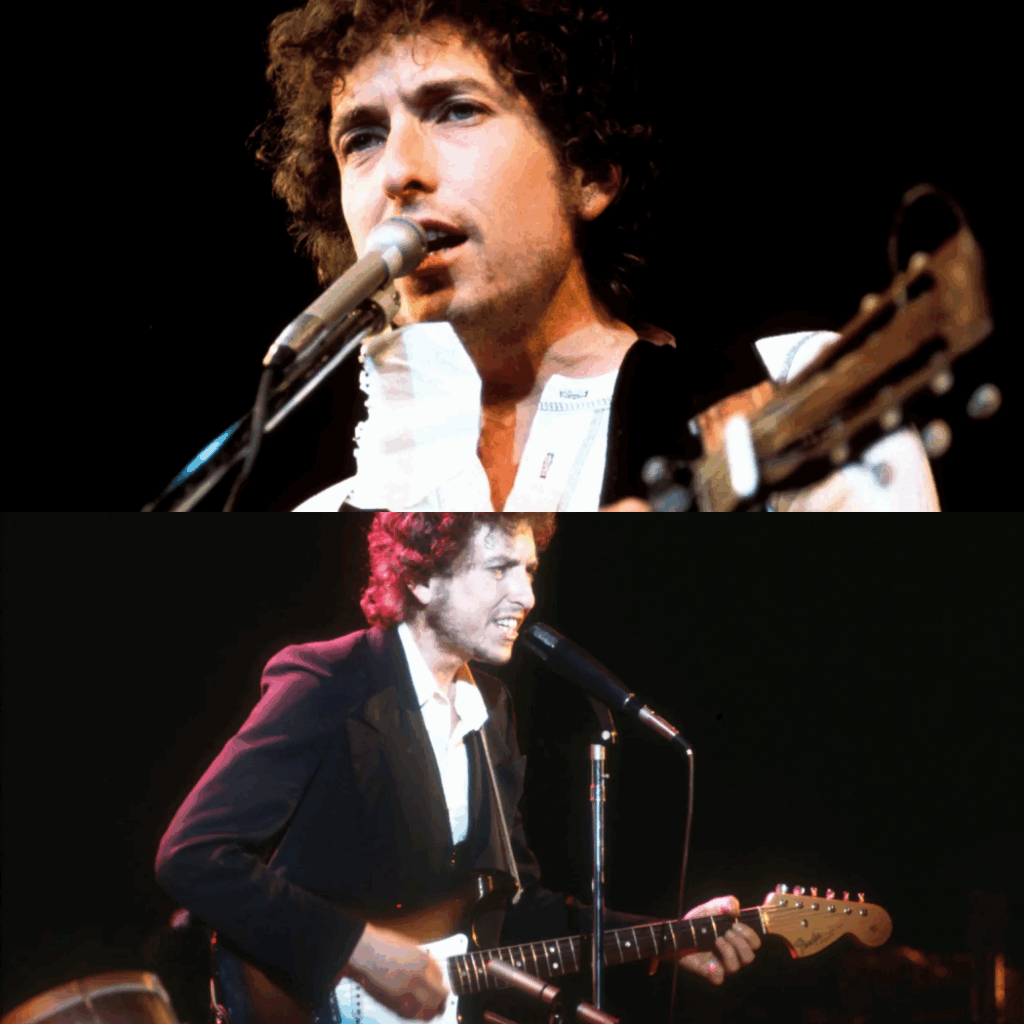

Sheridan tells me he aims to do “responsible storytelling”, to depict the moral consequences of certain behaviours and decisions. He says he was strongly influenced by Clint Eastwood’s 1992 film, Unforgiven, which “upended” the black-hat/white-hat conventions of the traditional Western. Eastwood “let the sheriff be a bully and the hero be this drunken, vicious killer”. He “shattered the myth of the American Western”, Sheridan says. “So when I stepped into that world, I wanted there to be real consequences. I wanted to never, ever shy away from, This was the price.”

A chance encounter

Though now a rich screenwriter, Sheridan still lives a version of the cowboy life. When he was growing up, his family had a ranch outside Waco, Texas, where he learnt to shoot and ride.

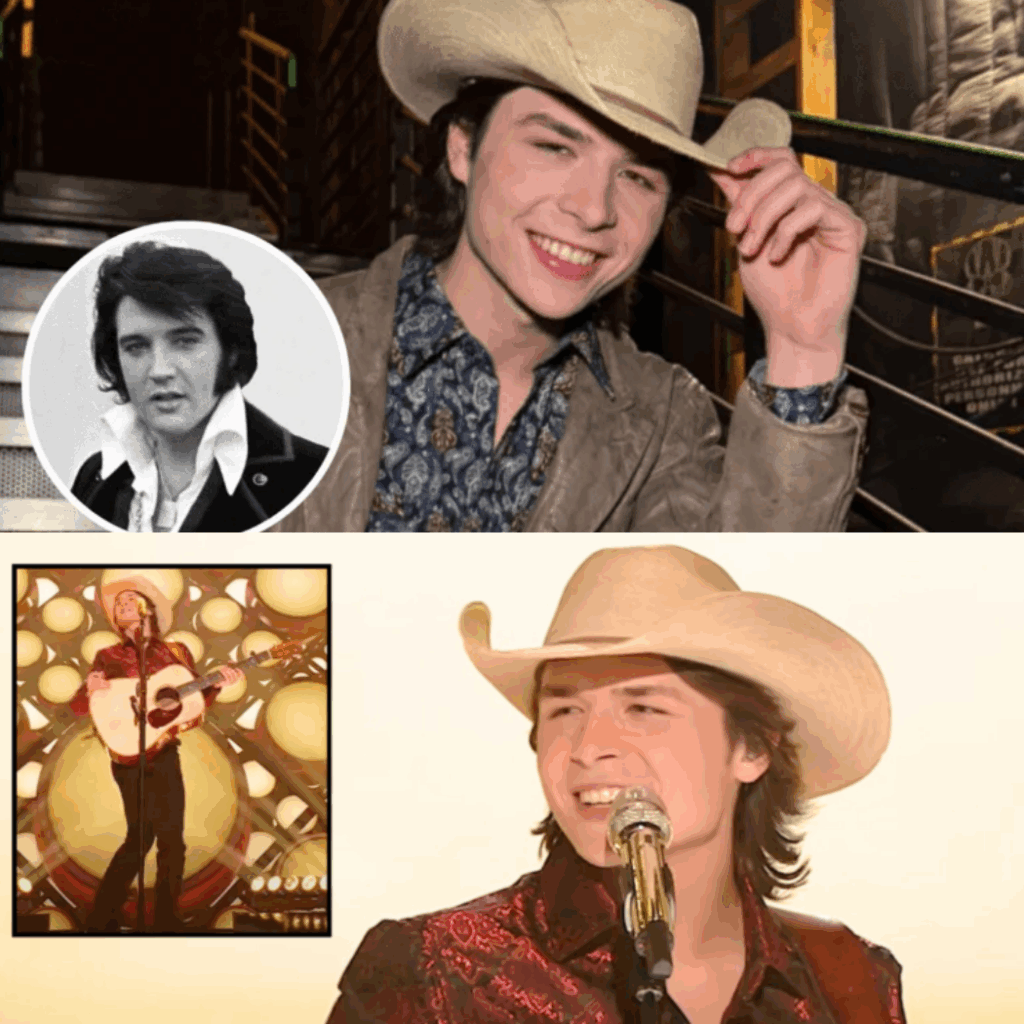

Though the mythology of his cowboy roots has been embellished over time – his father was a cardiologist, the ranch a weekend home – he is a genuinely skilled horseman. He has won thousands of dollars in “cutting” competitions, and he produces a reality show, The Last Cowboy, in which men and women compete in horse reining. In 2021, he was inducted into the Texas Cowboy Hall of Fame.

After what Sheridan has said was a difficult childhood – he spent a lot of time roaming the ranch in solitude – he dropped out of college at Texas State University and moved to Austin, where he did odd jobs such as house-painting and landscape work.

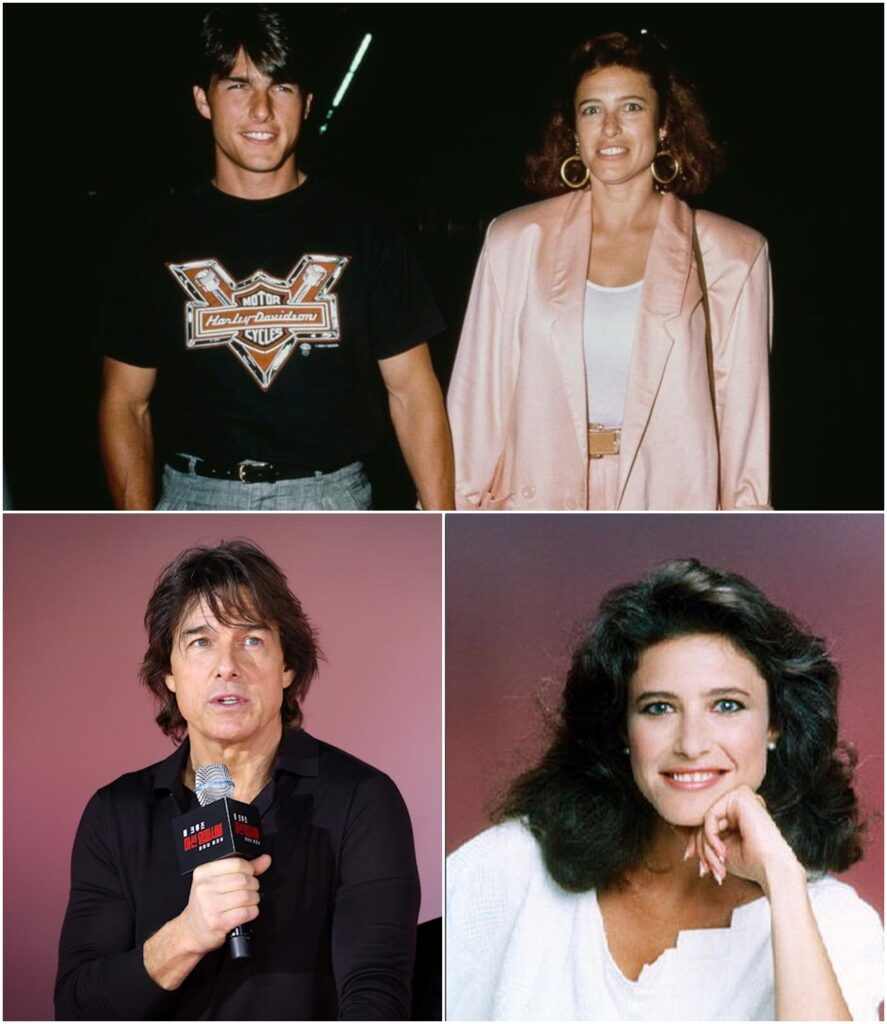

He has said a chance encounter with a talent scout in a mall provided a way into acting. A successful audition in Chicago eventually brought him to Los Angeles. Over time, he got bit parts on shows such as CSI, NYPD Blue, and Walker, Texas Ranger. He was working, but his career didn’t seem to be leading anywhere in particular. For a time, as he struggled, he lived in his car with his dog.

While Sheridan waited for his break, he started a business coaching other actors. Though he’d yet to win success himself, he found he was good at helping other actors hone their craft.

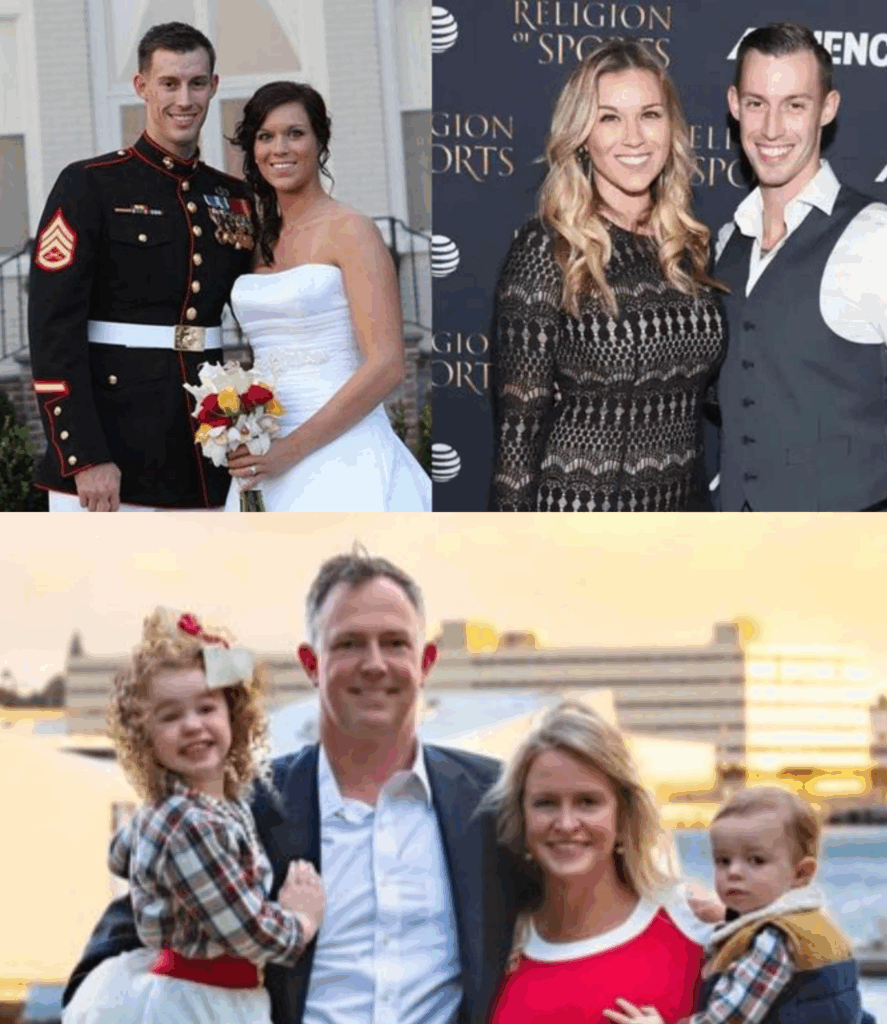

At 38, ancient for an actor, he earned a regular part as a deputy police chief on the FX network’s Sons of Anarchy, a TV drama centred on a motorcycle gang. From the outside, this was the kind of life that so many of his peers, still working as bartenders and baristas, dreamed of. But after two seasons, he decided it wasn’t sustainable. Yes, he was making more than $US100,000 a year. But there were costs: an agent, a manager. By then, he was married to his wife, Nicole, who was having a baby. When he asked the producers for a raise, they refused. So he decided he had to leave. Not just the show, but acting entirely.

Sheridan didn’t know what to do, or where to go. He talked with a friend about moving to Wyoming, where he might lead camping trips on horseback, put his cowboy skills to use. One of his coaching clients was intense Canadian-born actor Hugh Dillon.

Grim view of America

”I’m putting the script in a desk for 10 years until I can make it the way I want to make it,” he told Dillon. And he started writing a film instead.

By conventional storytelling logic, Sicario shouldn’t work. It’s unwieldy, the plot a bit tough to follow. As Sheridan himself has said of the movie, his first screenplay to become a film, it’s hard to know whom to root for.

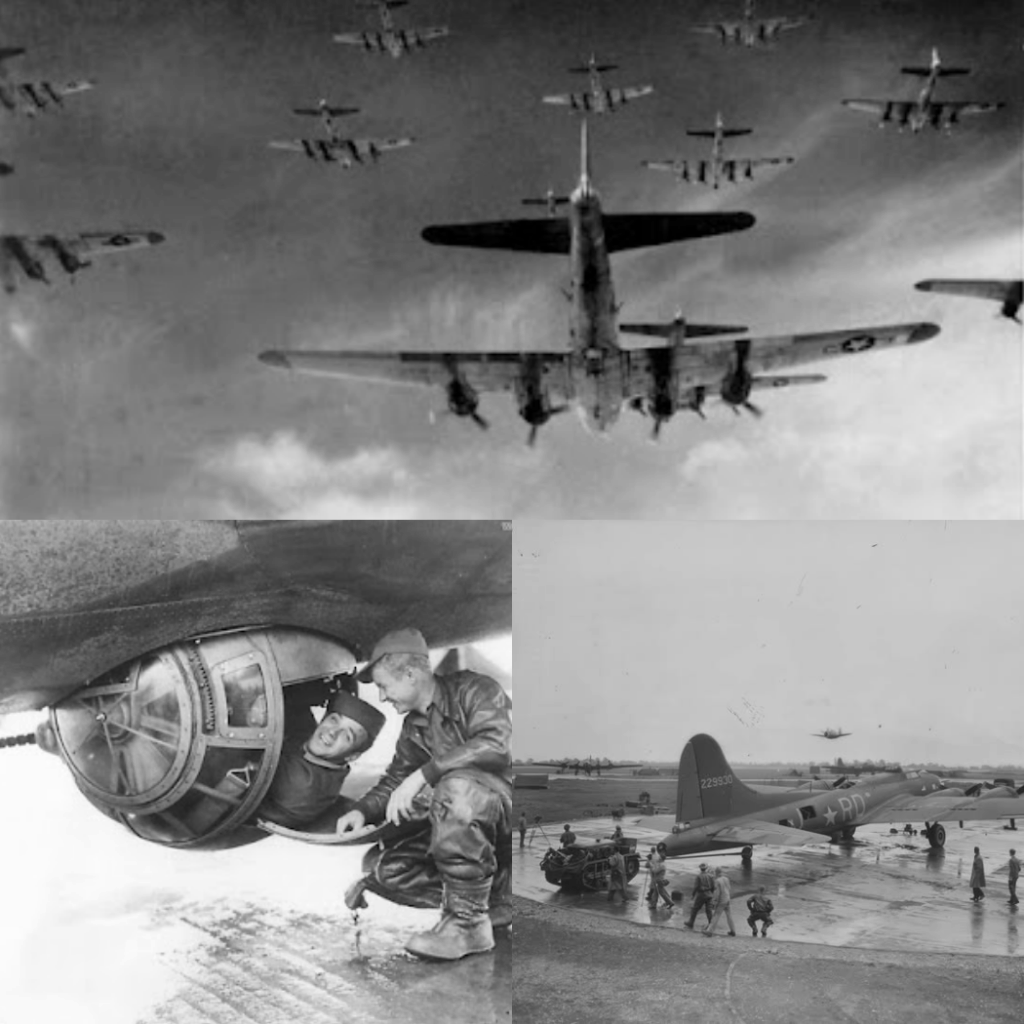

We’re just as lost as Kate Macer, the FBI agent played by Emily Blunt, who is trying to avoid getting killed by the ostensible “good guys” in the shadow war between the US government and Mexican drug cartels. Set along the El Paso–Juárez border, the film is violent and, in its refusal to provide any redemption or uplift, existentially bleak. Its vision of America and its institutions is grim.

Complex characters

However stripped down the scripts might be, Viacom executives were concerned that if Sheridan didn’t share the workload, he would drown. For Season 2, they gave him a writers’ room. It didn’t go well.

When the writers, who were mostly based in Los Angeles, came to the set, “Taylor refused to talk to them”, according to the Yellowstone veteran who spoke with me on condition of anonymity.

For Season 3, the writers’ room was gone.

Yellowstone was far from an instant hit. When Chris McCarthy, a longtime Viacom executive, gained oversight of Paramount Network in late 2019, he had never seen the show. The second season had just aired, and he had plenty of reasons to cancel it. Its numbers were decent, not spectacular.

HBO and Showtime had long ago made Sunday evenings the showcase for high-quality television drama, the last citadel of appointment viewing. So McCarthy moved it to prestige night. When the numbers started to grow, in 2021, Paramount took the next step, moving it from summer to autumn.

Embracing streaming

It worked. The Season 3 premiere earned 7.6 million viewers. Last year’s Season 4 premiere almost doubled that figure; its 12.7 million viewers made it the most-watched premiere since the Walking Dead season opener in 2017.

But McCarthy needed still more from Sheridan. Before McCarthy came on board, Viacom had sold off the streaming rights to some of its assets in what amounted to a shortsighted view of the cord-cutting market. (This is why earlier seasons of Yellowstone belong to Comcast, which airs the show on its Peacock streaming service.)

In early 2021, Viacom CBS belatedly embraced the streaming revolution, rebranding its CBS All Access service as Paramount+. Having seen Yellowstone buoy Paramount’s cable channel, McCarthy turned again to Sheridan to get the rechristened streaming service off the ground.

Paramount had already approved Mayor of Kingstown, the show that Sheridan had years ago co-created with Hugh Dillon. But it needed more programming, and needed it fast. Hence, the decision to “double down, triple down on Taylor”, as McCarthy put it, with 1883 and the parade of additional prequels and spin-offs that has followed.

In 2021, Paramount gave Sheridan a multiyear development deal that will reportedly pay him $US200 million. At the moment, he’s working on at least eight shows, which fall into two baskets. In the first are the programs he writes himself: Yellowstone and 1923 and Mayor of Kingstown and possibly 6666, as well as Lioness, starring Zoe Saldana, about a crew of female CIA operatives trying to bring down a terrorist organisation.

Lioness actually had a showrunner and a writers’ room, but sources told Variety that after the room finished, the producers and showrunner, Thomas Brady, had an amicable parting of the ways concerning creative differences, and Sheridan took over.

I thought back to a visit I’d made to Sheridan’s sprawling Bosque Ranch in Texas last year, when I’d talked with Jen Landon, who plays delightfully wacky Yellowstone wrangler Teeter, about how fractured American television and film viewership has become. Landon told me she knew a producer on Hell or High Water who had never watched Yellowstone. This was “somebody who would like to work with him again”, Landon said, and yet Yellowstone was somehow not on her cultural radar.

“There was such a need and a hunger for this show,” Landon said. “A demographic of people who I normally associate with not knowing how to open Netflix managed to find Paramount and watch this show because they needed it because they couldn’t relate to anything else.”

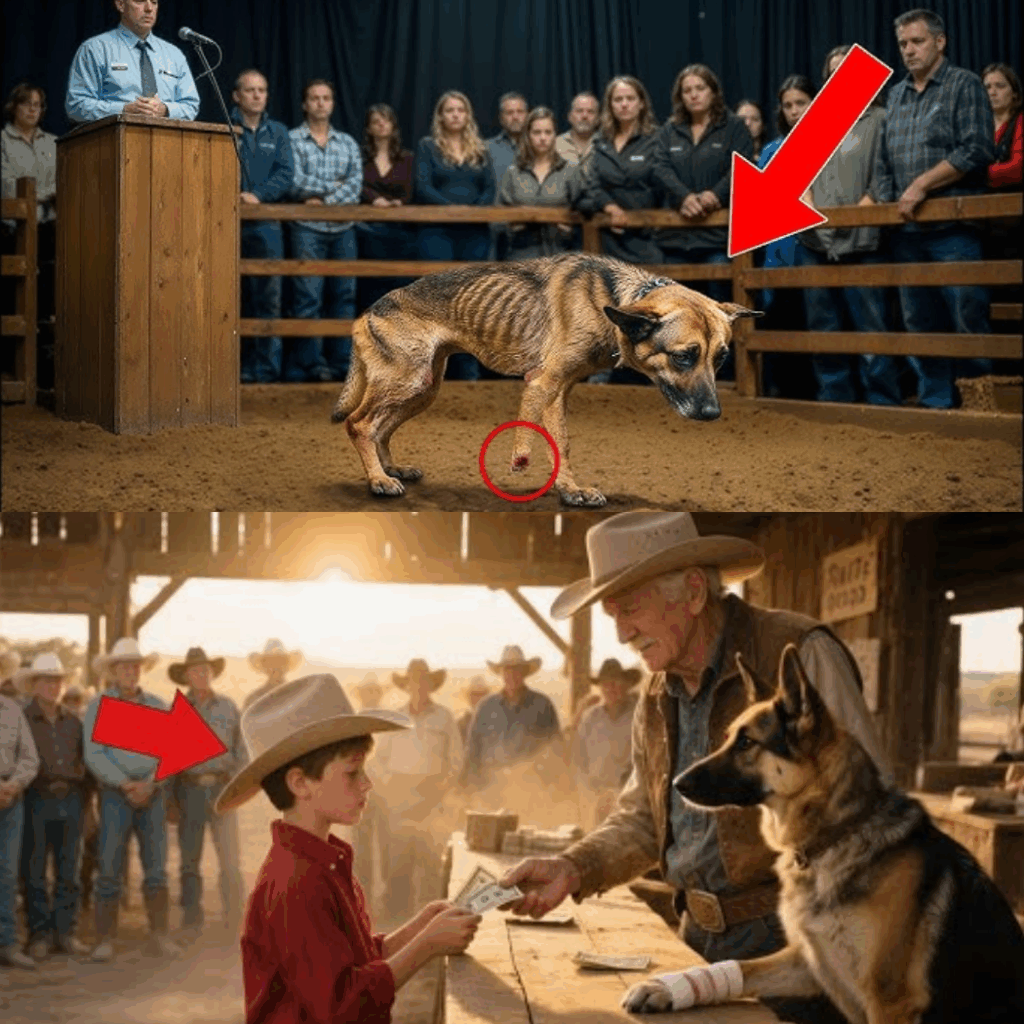

But what, exactly, are they relating to? Much of the show revolves around the Yellowstone bunkhouse, the rowdy, spartan home of the wranglers, where discipline is kept by a hierarchy that is almost primate-like in its rigidity. The alpha male, the lead ranch hand Rip, establishes and maintains his stature by fighting. Throughout the series, violence of various kinds is shown to be a necessary evil, whether to defend your family or your land or the existing social order, or simply to keep the peace. Controlled violence (cowboys beating the crap out of each other under supervision) can be a release valve to prevent worse violence (cowboys killing each other unsupervised).

The character for whom Sheridan seems to have the greatest contempt is John Dutton’s son, Jamie. Though he went off to Harvard Law at the behest of his father, who thought it would help him defend the ranch’s interest in court and in the Montana legislature, Jamie is seen by John Dutton as pathetically weak and untrustworthy because he wears nice suits and fights his battles with words and arguments, not fists and guns.

He achieves momentary redemption only when he’s sent, as punishment, to live as low man in the bunkhouse, shovelling manure and earning a more honest living for a while.

He knows it’s not sustainable. But he says this is a “three-to-five-year thing, at best – at least as far as me writing, directing, editing, casting” – not something he could keep up for 10 or 15 years. “I don’t know that I will ever have this creative freedom again,” he says. “Hopefully, I can ride off into the sunset before something tanks.”